Book notes: Molecular Evolution: A Statistical Approach by Ziheng Yang

Last modified: Post views:We decide to read the book Molecular Evolution: A Statistical Approach by Ziheng Yang, to gether on a weekly basis. Contents in this summary involve AI-generated text.

1. Models of nucleotide substitution

- We define $p$ distance as thr proportion of sites that differ between two sequences.

- The true evolutionary distance $d$ is the expected number of substitutions per site between two sequences.

- CTMC (Continuous Time Markov Chain): four nucleotides are states of the chain, it will reach to steady state with a stationary distribution, via a substitution rate matrix.

Markov models of nucleotide substitution and distance estimation

The JC69 model

- Jukes-Cantor 1969 model.

- The substitution rate matrix $Q$ is \(Q = \begin{pmatrix} -3\lambda & \lambda & \lambda & \lambda \\ \lambda & -3\lambda & \lambda & \lambda \\ \lambda & \lambda & -3\lambda & \lambda \\ \lambda & \lambda & \lambda & -3\lambda \end{pmatrix}\)

- The matrix of transition probability: $P(t) = e^{Qt}$. This is using Kolmogorov forward/backward? equation, where $\frac{dP(t)}{dt} = QP(t)$.

- We then use Taylor expansion to get $P(t) = I + Qt + \frac{Q^2t^2}{2!} + \cdots$.

- Essense of calculus by 3Blue1Brown.

- Chapman–Kolmogorov equation: $P_ij(t+s) = \sum_k P_ik(t)P_kj(s)$. This account for the multiple (hidden) states between $i$ and $j$.

- As $d=3\lambda t$, then $p(d) = 3p_1(t)=\frac{3}{4}-\frac{3}{4}e^{-4\lambda t}=\frac{3}{4}-\frac{3}{4}e^{-4d/3}$, then $\hat{d}=-\frac{3}{4}log(1-\frac{4}{3}\hat{p})$.

The K80 model

- Kimura 1980 model.

- Transitions: pyrimidine (T $\leftrightarrow$ C), purine (A $\leftrightarrow$ G).

- Transversion: (T, C $\leftrightarrow$ A, G).

- $d = (\alpha + 2\beta)t$.

- $\kappa = \frac{\alpha}{\beta}$.

- $E(S) = p_1(t)$.

- $E(V) = 2p_2(t)$.

- $\hat{d} = -\frac{1}{2} \log(1 - 2S - V) - \frac{1}{4} \log(1 - 2V)$.

HKY85, F84, TN93, etc.

TN93

- Tamura-Nei 1993 model.

- 7 parameters and 6 free parameters.

- $\pi_Y = \pi_T + \pi_C$ and $\pi_R = \pi_A + \pi_G$.

- $P(t)$ can be solved using spectral decomposition of $Q$.

- $Q = U \Lambda U^{-1}$.

- $\Lambda = \text{diag}\lbrace \lambda_1, \lambda_2, \lambda_3, \lambda_4 \rbrace$.

- $P(t) = U e^{\Lambda t} U^{-1} = U \text{diag}\lbrace e^{\lambda_1 t}, e^{\lambda_2 t}, e^{\lambda_3 t}, e^{\lambda_4 t} \rbrace U^{-1}$.

- Essense of linear algebra by 3Blue1Brown.

- Eigenvectors and eigenvalues with prerequisites:

- Linear transformations

- Matrix multiplication

- Determinants

- Linear systems

- Change of basis, Jennifer is a French as indicated in 3:21 of this video :D

- Eigenvectors and eigenvalues with prerequisites:

- $\lambda = -\sum_i \pi_i q_{ii} = 2\pi_T \pi_C \alpha_1 + 2\pi_A \pi_G \alpha_2 + 2\pi_Y \pi_R \beta$.

- $d = \lambda t$.

- Using $E(S_1), E(S_2), E(V)$ to estimate $\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \beta$.

- $\hat{d}$ can be represented as a function of nucleotide frequencies and $E(S_1), E(S_2), E(V)$.

HKY85 and F84

-

6 parameters and 5 free parameters.

- Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano 1985 model.

- Interesting fact: it should be called HKY84, misnamed in Yang 1994.

- Setting $\alpha_1 = \alpha_2 = \alpha$ or $\kappa_1 = \kappa_2 = \kappa$ in TN93 model.

- Felsenstein 1984 model.

- Setting $\alpha_1 = (1+\kappa/\pi_Y)\beta$ and $\alpha_2 = (1+\kappa/\pi_R)\beta$ in TN93 model.

- It is easier to derive a distance formula for F84 than for HKY85.

- Felsenstein 1981 model.

- Setting $\alpha_1 = \alpha_2 = \beta$ in TN93 model.

- A distance formula was derived by Tajima and Nei (1982).

- On a side note, Tajima and Nei (1984) is a classic paper on nucleotide diversity.

The transition/transversion rate ratio

- Three definitions:

- $E(S)/E(V) = p_1(t)/2p_2(t)$ under the K80 model (the uncorrected method).

- $\kappa = \alpha/\beta$ under the K80 model (corrected).

- $R = \alpha/2\beta$ under the K80 model (corredted). It’s called average transition/transversion ratio. More generally, $R = \frac{\pi_T q_{TC} + \pi_C q_{CT} + \pi_A q_{AG} + \pi_G q_{GA}}{\pi_T q_{TA} + \pi_T q_{TG} + \pi_C q_{CA} + \pi_C q_{CG} + \pi_A q_{AT} + \pi_A q_{AC} + \pi_G q_{GT} + \pi_G q_{GC}}$ under UNREST.

Variable substitution rates among sites

- Assuming the rate $r$ for any site is drawn from a gamma distribution.

- Models with Gamma distance denoted by a suffix ‘$+\Gamma$’.

- Gamma distribution have two parameters: shape $\alpha$ and scale $\beta$. The mean is $\alpha/\beta$, and the variance is $\alpha/\beta^2$. You can also consider them as number of Poisson process events of $\alpha$ with rate $1/\beta$.

- Note that the gamma distribution here sets $\alpha = \beta$ so that the mean equals to $1$.

- If a site has a rate $r$, the distance between sequences becomes $d = r t$.

- $p(d\cdot r)$ can be calculated by integrating the gamma distribution.

- For JC69 model, $p = \int_0^\infty \left( \frac{3}{4} - \frac{3}{4} e^{-4d \cdot r / 3} \right) g(r) \, dr = \frac{3}{4} - \frac{3}{4} \left( 1 + \frac{4d}{3\beta} \right)^{-\alpha}$.

- Similarly, one can derive a gamma distance under virtually every model for which a one-rate distance formula is available.

- It is well known that ignoring rate variation among sites leads to underestimation of both the sequence distance and the transition/transversion rate ratio.

Maximum likelihood estimation of distance

- The likelihood function is $L(\theta; X) = f(X\vert\theta)$.

- MLE is the value of $\theta$ that maximizes the likelihood function.

- Probability vs. Likelihood:

- Likelihood $\ne$ Probability: Likelihood does not sum to 1, unlike probability.

- Interpretation: Probability is understood by area under the curve, while likelihood is compared at specific points.

- Reparametrization: Likelihood is invariant under monotonic transformations, so MLEs remain unchanged.

- Nonlinear Effects: Nonlinear transformations alter probability density shapes, potentially changing modality.

The JC69 model

- The single parameter is the distance $d = 3\lambda t$. The data are two aligned sequences, each $n$ sites long, with $x$ differences.

- $p = 3p_1(t) = \frac{3}{4} - \frac{3}{4} e^{-4d/3}$.

- The likelihood function is $L(d; X) = {n\choose x}p^x(1-p)^{n-x}$.

- After reparametrization: $L(d; X) = (\frac{1}{4}p_1)^x (\frac{1}{4}p_0)^{n-x}$. (I think $\frac{1}{4}$ can be further dropped.)

- Two approaches to estimate confidence intervals:

- Normal approximation: $\hat{d} \pm 1.96 \sqrt{var({d})}$.

- Likelihood interval, based on likelihood ratio test: $\frac{1}{2}\chi^2_{1, 5\%} = 3.841/2 = 1.921$.

The K80 model

- $L(d, \kappa; n_S, n_V) = \left( \frac{p_0}{4} \right)^{(n - n_S - n_V)} \times \left( \frac{p_1}{4} \right)^{n_S} \times \left( \frac{p_2}{4} \right)^{n_V}.$

- $\frac{1}{2}\chi^2_{2, 5\%} = 5.991/2 = 2.995$.

Likelihood ratio test of substitution models

- For model comparison, if two models are nested, then the likelihood ratio test can be used.

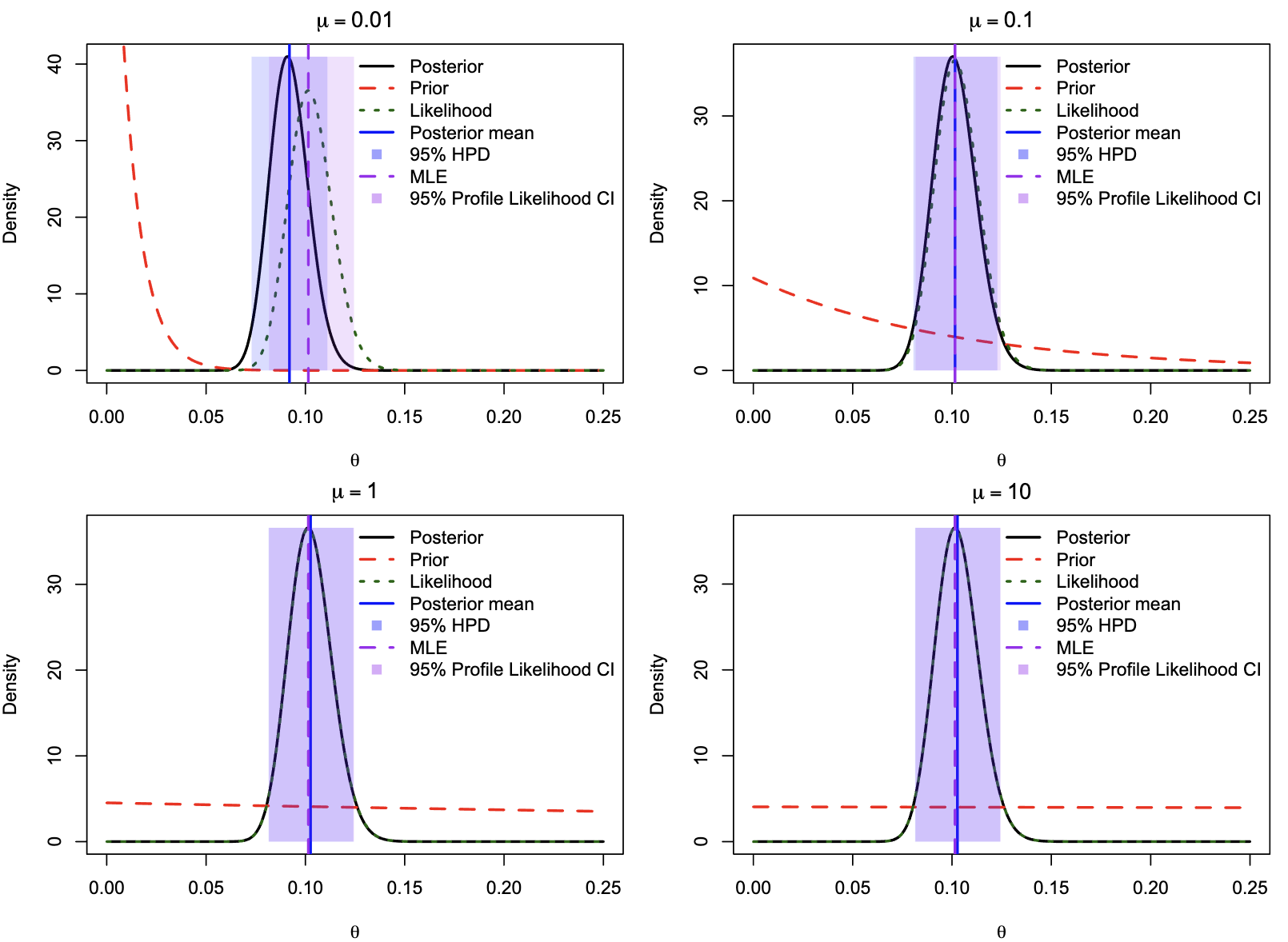

Profile and integrated likelihood

- The above approaches, estimating one parameter while ignoring the other, are called relative likelihood, pseudo likelihood or estimated likelihood.

- A more respective approach is profile likelihood.

- $\ell(d) = \ell(d, \hat{\kappa}_d)$, where $\hat{\kappa}_d$ is the MLE of $\kappa$ for the given $d$.

- This is a pragmatic approach that most often leads to reasonable answers.

- Integrated likelihood or marginal likelihood is the likelihood of the data given the model, averaged over the parameter space.

- It is possible to use a improper prior, such as a uniform distribution, to calculate the marginal likelihood.

- Integrated likelihood is always smaller than the profile likelihood.

Markov chains and distance estimation under general models

Distance under the unrestricted (UNREST) model

- Unlike the GTR model, UNREST does not assume time-reversibility.

- Here we consider a strand-symmetry model, where $q_{TC} = q_{AG}$.

- Equilibrium nucleotide frequencies ${\pi_T, \pi_C, \pi_A, \pi_G}$ perhaps by coincidence, can be estimated analytically.

- Identifiability Issues and Distance Calculation

- The model can, in theory, identify the root of a two-sequence tree.

- However, estimating both $t_1$ and $t_2$ separately leads to high correlation between estimates.

- The model has 13 parameters:

- 11 rate parameters in $Q$.

- 2 branch lengths $t_1, t_2$.

- Challenges:

- No analytical solution for MLEs.

- Complex eigenvalues make numerical estimation difficult.

- Many datasets do not provide enough information to estimate so many parameters.

- *Conclusion:-

- Although $t_1$ and $t_2$ are identifiable, their estimates are highly correlated.

- The UNREST model is not recommended for distance calculations.

Distance under the general time-reversible model

- Time-Reversibility in Markov Chains

- A Markov chain is time-reversible if: \(\pi_i q_{ij} = \pi_j q_{ji}, \quad \text{for all } i \neq j.\) This condition is known as detailed balance.

- Reversibility is a mathematical convenience, not necessarily a biological property.

- Models such as JC69, K80, F84, HKY85, and TN93 are all time-reversible.

- Rate Matrix for GTR Model

- The GTR (General Time-Reversible) model is defined using the rate matrix:

\(Q =

\begin{bmatrix}

\cdot & a\pi_C & b\pi_A & c\pi_G \\

a\pi_T & \cdot & d\pi_A & e\pi_G \\

b\pi_T & d\pi_C & \cdot & f\pi_G \\

c\pi_T & e\pi_C & f\pi_A & \cdot

\end{bmatrix}\)

- It has nine free parameters (six substitution rates + three equilibrium frequencies).

- The GTR (General Time-Reversible) model is defined using the rate matrix:

\(Q =

\begin{bmatrix}

\cdot & a\pi_C & b\pi_A & c\pi_G \\

a\pi_T & \cdot & d\pi_A & e\pi_G \\

b\pi_T & d\pi_C & \cdot & f\pi_G \\

c\pi_T & e\pi_C & f\pi_A & \cdot

\end{bmatrix}\)

- Simplification of Likelihood Computation

- Reversibility simplifies likelihood computation:

\(f_{ij}(t_1, t_2) = \sum_k \pi_k p_{ki}(t_1) p_{kj}(t_2) = \pi_i p_{ij}(t_1 + t_2).\)

- The second equality follows from reversibility.

- The third equality follows from the Chapman-Kolmogorov theorem.

- This allows estimation of total branch length instead of individual times.

- Reversibility simplifies likelihood computation:

\(f_{ij}(t_1, t_2) = \sum_k \pi_k p_{ki}(t_1) p_{kj}(t_2) = \pi_i p_{ij}(t_1 + t_2).\)

- Log-Likelihood Formulation

- The log-likelihood function is: \(\ell(t, a, b, c, d, e, f, \pi_T, \pi_C, \pi_A) = \sum_i \sum_j n_{ij} \log(\pi_i p_{ij}(t)).\)

- After scaling, the distance is defined as: \(d = -t \sum_i \pi_i q_{ii} = t.\)

- Note that distance formulae are not MLEs.

- Observed base frequencies are not MLEs of the base frequency parameters.

- All 16 site patterns have distinct probabilities in the likelihood function but are collapsed in distance formulae (e.g., TT, CC, AA, GG).

- Despite this simplification, distance formulae still approximate MLEs well.

- Pairwise comparisons sum up branch lengths but may overestimate distances.

- Likelihood-based methods (ML, Bayesian) provide better phylogenetic estimates.

2. Models of amino acid substitution and codon substitution

Models of amino acid replacement

Empirical models

- Empirical models:

- The rates of substitution are estimated directly from observed sequence variations, without explicitly considering the biological processes that drive these substitutions.

- They are statistical and data-driven, without needing detailed knowledge of the underlying biological mechanisms.

- Mechanistic models:

- They are based on the underlying biological processes that drive sequence evolution.

- They offer more interpretative power, helping to understand the biological mechanisms and evolutionary forces that shape protein sequences.

- Empirical models of amino acid substitution are all constructed by estimating the relative substitution rates between amino acids under the GTR model.

- Under GTR, $\pi_i q_{ij} = \pi_j q_{ji}$ and $\pi_i p_{ij}(t) = \pi_j p_{ji}(t)$, with $i,j \in {1,2,\ldots,20}$.

- $q_{ij}$ or $s_{ij}$ are the amino acid exchangeabilities.

- Dayhoff (1978) and JTT (1992): fixed estimates.

- Dayhoff+F, JTT+F, add 19 free parameters by replacing the $\pi_i$ in the empirical matrices by the frequencies estimated from the data.

- WAG (2001), LG (2008) etc. use maximum likelihood to estimate the exchangeabilities.

- BLOSUM (1992) focus on more conserved regions in protein families.

- BLOSUM62 is often considered roughly equivalent to PAM250.

- Some features in the estimated exchangeabilities are in fact as expected from the physico-chemical properties of amino acids. Also the larger number of substitution events needed to change between two amino acids, the lower the exchangeability. Evidence by comparing the exchangeabilities in normal proteins and mitochondrial proteins (codon table is different).

Mechanistic models

- Yang et al. (1998) implemented a few mechanistic models, taking account of e.g. different mutation rates between nucleotides, translation of the codon triplet into amino acid, and acceptance or rejection of the amino acid due to selective pressure on the protein.

- The improvement was not extraordinary, perhaps reflecting our poor understanding of which of the many chemical properties are most important and how they affect amino acid substitution rates

Among-site heterogeneity

- Dayhoff+$\Gamma$, JTT+$\Gamma$, etc. are similar to the nucleotide models with among-site rate variation. $rQ$ is the rate matrix for a site.

- Recall that in the Gamma model, we delibrately set $\alpha = \beta$ so that the mean is 1. The higher the $\alpha$, the more concentrated the distribution is around the mean.

- Site-specific amino acid frequency parameters is also possible. For each (group of) site, this reflects how likely different amino acids are to appear (different patterns). However, this approach adds many parameters, making it challenging for maximum likelihood (ML) analysis.

Estimation of distance between two protein sequences

The Poisson model

- The number of substitutions over time $t$ can be a Poisson-disributed random variable under rate $\lambda$.

- Similar to JC69 model, the expected number of substitutions is $d = 19\lambda t$.

- Similarly, the expected distance is $\hat{d} = -\frac{19}{20}\log(1-\frac{20}{19}\hat{p})$. If $p > \frac{19}{20}$, then $\hat{d} = \infty$.

Empirical models

- We deliberately set $-\sum_i \pi_i q_{ii} = 1$ so that $d = 1 \times t$, the mean distance is 1.

- Under GTR, the log-likelihood function is $\ell(t) = \sum_i \sum_j n_{ij} \log(\pi_i p_{ij}(t))$.

- We can also use $p$ distance, $p = 1 - \sum_i \pi_i p_{ii}(t)$, but this will lose information, nevertheless, should approximate the MLE well.

Gamma distance

- Under something similar to JC69, adding a gamma distribution to the rate of substitution, we have $\hat{d} = \frac{19}{20} \alpha [(1 - \frac{20}{19}\hat{p})^{-\frac{1}{\alpha}} - 1]$. This is obtained by integration of the gamma distribution over the formula for $p$ distance (see formula 1.35).

- For empirical models, use ML to estimate the distance.

Models of codon substitution

The basic model

- The instantaneous rate matrix $Q$ is a $61 \times 61$ matrix.

- \[q_{IJ} = \begin{cases} 0, & \text{if I and J differ at two or three codon positions,} \\ \pi_J, & \text{if I and J differ by a synonymous transversion,} \\ \kappa\pi_J, & \text{if I and J differ by a synonymous transition,} \\ \omega\pi_J, & \text{if I and J differ by a nonsynonymous transversion,} \\ \omega\kappa\pi_J, & \text{if I and J differ by a nonsynonymous transition.} \end{cases}\]

- $\omega$ is the nonsynonymous/synonymous rate ratio. If $\omega > 1$, it indicates positive selection, if $\omega < 1$, it indicates purifying selection.

- Fequal model: $\pi_i = 1/61$.

- F1x4 model, F3x4 model, and F61 model: $\pi_i$ are estimated from the data.

- The rate matrix $Q$ time-reversible as it meets the detailed balance condition.

Variations and extensions

- The Muse-Gaut model (1994) is a generalization of the basic model.

- Simialr to F3x4 with omega?

- The mutation-selection (FMutSel) model.

- mutation bias: $\mu_{ij} = a_{ij} \pi^*_j$.

- selection: $S_{IJ} = f_J - f_I$.

- The probability of fixation of the mutation is $P_{IJ} = \frac{2S_{IJ}}{1 - e^{-2NS_{IJ}}}$.

- The $\omega$ ratio does not have to be a single parameter, it can be modelled by physico-chemical properties, e.g. $\omega_{IJ} = ae^{-bd_{IJ}}$, where $d_{IJ}$ is the chemical distance between amino acids.

- Or you can model $\omega$ by a few pre-specified categories of nonsynonymous substitutions.

- Allowing double or triple mutations should be more realistic. It is common to observe ‘synonymous’ differences between the two sets of serine codons (TCN and AGY) which cannot exchange by a single nucleotide mutation. Some people argue this is because separate lines of descent rather than multiple mutations.

Estimation of $d_S$ and $d_N$

- Recall that the evolutionary distance $d$ focuses on the entire sequence, now we want to separate the distance by synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations, then we get $d_S$ and $d_N$.

- Definitions: The number of synonymous/nonsynonymous substitutions per synonymous/nonsynonymous site.

- Methods: Counting and ML.

Counting methods

- Three steps:

- Count the number of synonymous and nonsynonymous sites.

- Count the number of synonymous and nonsynonymous differences.

- Calculate the proportions of differences and correct for multiple hits.

- A basic model is Nei and Gojobori (1986) (NG86), which used equal weights for all codon positions.

Counting sites ($S$ and $N$)

- Introducing NG86 model, then relax the model with unequal transition and transversion rates and unequal codon usage. Different methods often produce very different estimates.

- There are three sites in a codon, and nine immediate neighbors.

- To calculate the synonymous and nonsynonymous sites, we need to multiply the synonymous/nonsynonymous probabilities (from the nine neighbors) by 3 sites. (Check Table 2.5)

Counting differences ($S_d$ and $N_d$)

- If two codons only differ by one nucleotide, then it is trivial to count the synonymous and nonsynonymous differences. (Check Table 2.6)

- If two codons differ by two or three nucleotides, there exist two or six possible paths to reach the codon, respectively.

- Weighting the paths needs knowledge.

Correcting for multiple hits

- We now have the $p$ distance, $p_S = S_d/S$ and $p_N = N_d/N$.

- The Jukes-Cantor correction is $d_S = -\frac{3}{4}\log(1 - \frac{4}{3}p_S)$ and $d_N = -\frac{3}{4}\log(1 - \frac{4}{3}p_N)$.

- This is logically flawed (Lewontin 1989), as JC69 assumes equal rates of substitution for all three other nucleotides, but when focusing on synonymous/nonsynonymous sites only, each nucleotide does not have three other nucleotides to change into.

Transition–transversion rate difference and codon usage

- From codon table, we see transitions at the third codon positions are more likely to be synonymous than transversions are. Therefore, a higher transition/transversion rate can lead to more synonymous substitutions, not necessarily due to selection. Ignoring this can lead to underestimation of $S$ (not $S_d$) and overestimation of $N$, and overestimation of $d_S$ and underestimation of $d_N$.

- The below methods classified codon positions into nondegenerate, two-fold degenerate, and four-fold degenerate sites, based on the number of synonymous substitutions possible. Note that some of the codons in fact do not fall into these categories, different methods may have different ways to deal with them.

- LWL85 Method (Li, Wu, and Luo, 1985):

- Counts two-fold degenerate sites as 1/3 synonymous and 2/3 nonsynonymous under the assumption of equal mutation rates.

- The distances are calculated using the total numbers of sites in different degeneracy classes and the estimated transition and transversion counts.

- LPB93 Method (Li, Pamilo, and Bianchi, 1993):

- Adjusts for transition–transversion rate bias (which was ignored by 1/3 and 2/3 approximation in LWL85).

- Uses the transition distance at four-fold sites to estimate $d_S$ and an averaged transversion distance at nondegenerate sites for $d_N$.

- Assuming that the transition rate is the same at the two-fold and four-fold sites; the transversion rate is the same at the nondegenerate and two-fold sites.

- LWL85m Method:

- A refinement of LWL85 that replaces the 1/3 assumption with an estimated proportion ($\rho$) of two-fold degenerate sites that are synonymous.

- Uses the ratio of transition and transversion distances at four-fold sites to estimate $\kappa$ (transition/transversion rate ratio).

- Alternative Approaches:

- Ina (1995) proposed not partitioning sites by codon degeneracy but instead weighting transitions and transversions based on neighboring codons (See Table 2.5).

- Consideration of unequal codon frequencies was introduced by Yang and Nielsen (2000), as previous models assumed equal codon frequencies, which is unrealistic.

- Example 2.2 is useful for understanding the above calculations.

- In Table 2.8, we see S are larger in LWL85m and Ina95, as they accounted for underestimation of S by considering ts/tv ratio, but ironically, they led to even more biased results, because they did not consider codon usage bias at the same time.

Maximum likelihood methods

- Under the basic model for codon substitution, which is a GTR again.

- Parameters estimated:

- $t$ (sequence divergence time or distance),

- $\kappa$ (transition/transversion rate ratio),

- $\omega$ (nonsynonymous/synonymous rate ratio),

- Codon frequencies (either fixed or estimated from the data), can be Fequal, F1x4, F3x4, or F61.

- $d_S$ and $d_N$ are then computed based on these ML estimates.

- Refer to Table 2.8, the Fequal with $\kappa=1$ is similar to NG86, and Fequal with $\kappa$ estimated is similar to LWL85, LPB93 and Ina95.

- Note that incorporating the transition–transversion rate difference has had much greater effect on the numbers of sites ($S$ and $N$) than on the numbers of substitutions ($S_d$ and $N_d$).

Comparing methods

- Estimation Bias and Model Effects:

- Ignoring Transition–Transversion Rate Differences:

- Leads to underestimation of synonymous sites ($S$) and overestimation of nonsynonymous sites ($N$).

- Results in overestimation of $d_S$ and underestimation of $\omega = d_N/d_S$.

- Ignoring Unequal Codon Usage:

- Has the opposite effect compared to ignoring transition–transversion rates.

- Leads to overestimation of $S$ and underestimation of $d_S$, which in turn overestimates $ω$.

- Codon frequency biases can sometimes override the effects of transition–transversion biases.

- The NG86 method, which ignores both transition–transversion differences and codon usage, sometimes produces more reliable estimates than models that only accommodate transition–transversion biases but ignore codon usage.

- Effect of Model Assumptions on Similar Sequences:

- When sequences are highly similar, different methods can produce very different estimates.

- Unlike nucleotide models, where distance estimates converge at low sequence divergences, codon-based models remain highly sensitive to assumptions.

- Importance of Model Assumptions:

- At low or moderate sequence divergences, different (counting or ML) methods produce similar results if they share the same assumptions.

- However, different counting/likelihood methods produce highly variable results because of differnt assumptions (e.g., $\kappa = 1?$ and codon bias).

- Ignoring Transition–Transversion Rate Differences:

- Advantages of the Likelihood Method Over Counting Methods:

- Conceptual simplicity

- Counting methods struggle with different transition/transversion rates and unequal codon frequencies.

- Some counting methods attempt to estimate $\kappa$, but this is challenging.

- Counting methods rely on nucleotide-based corrections for multiple hits, which can be logically flawed (mentioned under formula 2.15).

- Likelihood methods incorporate these complexities naturally without requiring correction formulas.

- No need for manual classification of synonymous vs. nonsynonymous substitutions, as these are inferred probabilistically.

- Easier to Incorporate Realistic Codon Models

- Likelihood methods can incorporate sophisticated codon substitution models.

- Example: GTR-style mutation models or HKY85-type models can be used in likelihood calculations.

- Conceptual simplicity

More distances and interpretation of the $d_N/d_S$ ratio

More distances based on the codon model

- Additional Distance Measures in the Codon Model

- Since we can get the expected number of substitutions from codon $i$ to codon $j$ over time $t$ is given by $\pi_i q_{ij} t$.

- We can calculate many other distances, not limited to $d_N$ and $d_S$, based on:

- Transition vs. transversion substitutions.

- Codon position-specific changes (first, second, third codon positions).

- Conservative or radical amino acid changes, etc.

- Distances at Different Codon Positions

- Distances at the first, second, and third codon positions can be calculated separately:

- $d_{1A}, d_{2A}, d_{3A}$ → After selection on the protein.

- $d_{1B}, d_{2B}, d_{3B}$ → Before selection on the protein (fixing $\omega = 1$).

- Distances at the first, second, and third codon positions can be calculated separately:

- Distance $d_4$ (Four-Fold Degenerate Sites)

- $d_4$ represents substitutions at four-fold degenerate sites in the third codon position.

- Used as an approximation of the neutral mutation rate.

Estimation of $d_S$ and $d_N$ in comparative genomics

- Time Scale Matters

- Estimating $d_S$ and $d_N$ requires a balance—sequences should be neither too similar nor too divergent.

- If species are too distantly related, synonymous substitutions may reach saturation, making $d_S$ unreliable.

- Estimates of $d_S > 3$ should be treated with caution, as high divergence leads to indistinguishable evolutionary distances.

- Solutions for High Divergence

- A phylogenetic approach can break long evolutionary distances into shorter branches by including multiple species.

- Issues with Low Divergence

- When sequences are too similar (e.g., within the same species or bacterial strains), $d_N/d_S$ estimates become unreliable.

- Observed bias: $d_N/d_S$ tends to decrease with increasing divergence, possibly due to MLE biases and correlations between parameter estimates.

- In within-population comparisons, deleterious nonsynonymous mutations may persist longer before being removed by selection, inflating $d_N/d_S$ at short timescales.

3. Phylogenetic reconstruction: overview

3.1 Tree concepts

Terminology

- Nodes (vertices) and branches (edges).

- Molecular clock: the rate of evolution is constant over time; Midpoint rooting: the root is placed at the midpoint of the longest path between two tips.

- Newick format:

(A:0.1,B:0.2,(C:0.3,D:0.4):0.5); Nexus format:#NEXUS; BEGIN TREES; TREE tree1 = (A:0.1,B:0.2,(C:0.3,D:0.4):0.5); END; - Bifurcating and multifurcating trees; fully resolved and polytomous trees.

- The total number of possible topologies of a n-tip rooted tree: $\frac{(2n-3)!}{2^{n-2}(n-2)!}$ (this is not hard to derive).

- Labelled histories (ranked trees): also considering the order of parallel internal nodes. We use coalescent process to calculate the total number of possible labelled histories for a n-tip tree: $\frac{n!(n-1)!}{2^{n-1}}$.

- Partition distance, also called Robinson-Foulds distance, is the number of bipartitions that are present in one tree but not in the other. It is a measure of the topological difference between two trees.

- The Kuhner-Felsenstein distance (1994) is a generalization of the Robinson-Foulds distance that considers branch lengths, by summing the absolute differences in branch lengths for each bipartition.

- Strict-consensus tree and majority-rule consensus tree.

- Monophyly and two types of non-monophyly: paraphyly (contains an ancestor but only some of its descendants) and polyphyly (contains various organisms with no recent common ancestor).

- Gene tree and species tree can mismatch under a relaxed molecular clock, if the evolutionary rate varies among lineages. As the distance does not reflect the relatedness of the species.

- The mismatch can also happen even under a fixed molecular clock, if the ancestral polymorphism is high and cause incomplete lineage sorting; and if with gene duplication and loss, or lateral (horizontal) gene transfer (LGT).

Classification of tree reconstruction methods

- Distance-based methods (e.g., Neighbor-Joining) convert sequences into a matrix of pairwise distances, then cluster the taxa to form a tree.

- Character-based methods (e.g., Maximum Parsimony, Maximum Likelihood, Bayesian) work directly with the alignment, examining each nucleotide or amino acid position.

- Model-based methods (like Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian approaches) explicitly use substitution models to account for how sequences evolve. Parsimony methods do not specify a detailed evolutionary model but instead look for the tree requiring the fewest changes. Distance-based methods often assume simpler models to correct raw pairwise distances.

3.2 Exhaustive and Heuristic Tree Search (for Optimality-Based Methods)

3.2.1 Exhaustive Tree Search

- Calculate score for every possible tree. Guaranteed to find the best tree.

- Feasible only for small datasets (e.g., < 10-12 taxa) due to the vast number of trees.

- Branch-and-bound can speed up exhaustive search for parsimony but not significantly for likelihood.

3.2.2 Heuristic Tree Search

Used when exhaustive search is impossible. Not guaranteed to find the optimal tree.

- Hierarchical Cluster Algorithms:

- Stepwise/Sequential Addition (Agglomerative): Add taxa one by one to a growing tree, choosing the best local placement at each step (Fig. 3.13). Order of addition matters; random addition orders run multiple times are common.

- Star Decomposition (Divisive): Start with a star tree. Iteratively join the pair of taxa that gives the best improvement to the tree score, reducing the central polytomy until fully resolved (Fig. 3.14).

- Tree Rearrangement / Branch Swapping (Hill-Climbing) (3.2.3):

- Start with an initial tree (random, NJ, or from cluster methods).

- Generate “neighbor” trees by local perturbations.

- Move to the neighbor with the best score. Repeat until no improvement.

- Types of Swaps (increasing neighborhood size and computational cost):

- Nearest Neighbor Interchange (NNI): Swaps subtrees around an internal branch (Fig. 3.15). Each internal branch gives 2 NNI neighbors. Total $2(n-3)$ neighbors.

- Subtree Pruning and Regrafting (SPR): Prune a subtree and reattach it to any other branch in the remaining tree (Fig. 3.16a).

- Tree Bisection and Reconnection (TBR): Break an internal branch to get two subtrees. Reconnect them by joining any branch from one to any branch of the other (Fig. 3.16b). Generates more neighbors than SPR.

- Local Peaks in Tree Space (3.2.4): Heuristic searches can get stuck in local optima (a tree better than its immediate neighbors, but not globally best) (Fig. 3.17, 3.18). Larger tree space for more taxa makes this a bigger problem.

3.2.5 Stochastic Tree Search

Algorithms that can escape local optima by allowing occasional “downhill” moves.

- Simulated Annealing: Modifies objective function early on (“heating”) to allow more exploration, gradually “cools” to greedy uphill search.

- Genetic Algorithm: Maintains a “population” of trees, uses “mutation” and “recombination” to generate new trees, “fitness” (optimality score) determines survival.

- Bayesian MCMC: Statistical approach producing point estimates and uncertainty measures. Allows downhill moves based on probabilities.

3.3 Distance Matrix Methods

Two steps: 1. Calculate pairwise distances. 2. Reconstruct tree from distance matrix.

3.3.1 Least-Squares (LS) Method

- Estimates branch lengths to minimize sum of squared differences between observed ($d_{ij}$) and tree-path (${\delta}{ij}$) distances: $S = \sum{i<j} (d_{ij} - {\delta}_{ij})^2$. (Eq 3.5)

- The tree with the minimum $S$ is the LS tree.

- Ordinary Least Squares (OLS): Assumes errors in $d_{ij}$ are independent and have equal variance. Usually incorrect (larger distances have larger variance; shared branches induce correlations).

- Weighted Least Squares (WLS): Weights terms by $w_{ij} = 1/\text{var}(d_{ij})$ or $w_{ij} = 1/d_{ij}^2$ (Fitch & Margoliash). Generally better than OLS.

- Generalized Least Squares (GLS): Accounts for correlations (covariances) as well. Computationally intensive, rarely used.

- Branch lengths can be constrained to be non-negative (more realistic but computationally harder).

3.3.2 Minimum Evolution (ME) Method

- Selects the tree with the minimum “tree length” (sum of all branch lengths). Branch lengths often estimated by LS.

- Plausible heuristic: true tree likely involves minimal total evolution.

- Many variations based on how branch lengths are estimated (OLS, WLS, GLS) and how tree length is defined (e.g., sum of all, only positive, or absolute values of branch lengths). (Table 3.5)

3.3.3 Neighbour-Joining (NJ) Method (Saitou & Nei, 1987)

- Divisive cluster algorithm; does not assume clock; produces unrooted trees. Fast and widely used.

- Starts with a star tree. Iteratively joins a pair of nodes $(i,j)$ that minimizes: $Q_{ij} = (r-2)d_{ij} - \sum_{k \neq i,j} (d_{ik} + d_{jk})$ (where $r$ is current number of nodes). (Eq 3.8)

- The joined pair is replaced by a new internal node, distances updated, process repeats.

- Justification: NJ is an ME method, but it minimizes a specific tree length definition by Pauplin (2000) (Eq 3.13), not the OLS tree length. This “balanced ME” criterion often performs better than OLS-based ME.

- BIONJ, WEIGHBOR: Modifications incorporating variance/covariance of distances, can improve accuracy.

3.4 Maximum Parsimony (MP)

3.4.1 Brief History

Originated from minimizing changes for discrete morphological data, later applied to molecular data.

3.4.2 Counting Minimum Changes

- Site Length: Minimum changes at one site on a given tree.

- Tree Length/Score: Sum of site lengths over all sites.

- Most Parsimonious Tree: The tree with the smallest tree length.

- Ancestral Reconstruction: Assigning states to internal nodes. The one yielding minimum changes is the Most Parsimonious Reconstruction (MPR). Fitch (1971b) and Hartigan (1973) algorithms find this.

- Informative Sites for Parsimony: Must have at least two character states, each appearing at least twice (e.g., xxyy, xyxy, xyyx for 4 taxa). Constant and singleton sites are uninformative. This concept is specific to parsimony.

3.4.3 Weighted Parsimony and Dynamic Programming (Sankoff, 1975)

- Assigns different costs (weights) to different types of changes (e.g., transitions vs. transversions).

- Sankoff’s Algorithm: A dynamic programming approach.

- For each node $i$ and each possible state $x$ at that node, calculate $S_i(x)$: minimum cost for the subtree defined by node $i$ (including its ancestral branch), given state $x$ at its parent.

- Proceeds from tips towards the root.

- For a tip $i$: $S_i(x)$ is simply the cost of change from parent state $x$ to observed tip state.

- For an internal node $i$ with parent state $x$ and daughter nodes $j, k$: $S_i(x) = \min_y [c(x,y) + S_j(y) + S_k(y)]$ (Eq 3.14), where $y$ is the state at node $i$.

- The minimum cost for the whole tree is found at the root (Eq 3.15).

- A second “down pass” (traceback) identifies the states at internal nodes that achieve this minimum cost. (Fig 3.24)

3.4.4 Probabilities of Ancestral States

Parsimony reconstructs ancestral states but doesn’t give probabilities. This requires a model of evolution (discussed in likelihood chapter).

3.4.5 Long-Branch Attraction (LBA)

- Parsimony’s major inconsistency problem (Felsenstein, 1978b).

- If the true tree has two long branches separated by a short internal branch (Fig 3.25a), parsimony tends to incorrectly group the two long branches (Fig 3.25b).

- Due to parsimony’s failure to correct for multiple (parallel/convergent) changes on long branches.

4. Maximum likelihood methods

This chapter focuses on the calculation of likelihood for multiple sequences on a phylogenetic tree. It builds upon Markov chain theory and ML estimation principles from Chapter 1.

4.1 Introduction

Two main applications of ML in phylogenetics:

- Parameter Estimation & Hypothesis Testing (Fixed Topology): Estimating parameters of an evolutionary model (e.g., branch lengths, substitution rates) and testing hypotheses about the evolutionary process, assuming the tree topology is known. ML provides a powerful and flexible framework for this.

- Tree Topology Inference: Maximizing the log-likelihood for each candidate tree by optimizing its parameters. The tree with the highest optimized log-likelihood is chosen as the best estimate. This is a model comparison problem.

4.2 Likelihood Calculation on Tree

4.2.1 Data, Model, Tree, and Likelihood

- Data ($X$): An alignment of $s$ sequences, each $n$ sites long. $x_{jh}$ is the $h^{th}$ nucleotide in the $j^{th}$ sequence. $x_h$ is the $h^{th}$ column (site) in the alignment.

- Model: e.g., K80 model. Assumes sites evolve independently and lineages evolve independently.

- Tree: (e.g., Fig 4.1 for 5 species). Tips are observed sequences. Internal nodes are ancestral. Branch lengths ($t_i$) are expected number of substitutions per site.

- Parameters ($\theta$): Collectively, all branch lengths and substitution model parameters (e.g., $\kappa$ for K80).

- Likelihood of Alignment: Due to site independence, $L(\theta) = f(X\vert \theta) = \prod_{h=1}^{n} f(x_h\vert \theta)$ (Eq 4.1)

- Log-Likelihood: $l(\theta) = \log{L(\theta)} = \sum_{h=1}^{n} \log{f(x_h\vert \theta)}$ (Eq 4.2)

- Likelihood for a Single Site ($f(x_h\vert \theta)$): Sum over all possible states ($x_0, x_6, x_7, x_8$ for internal nodes 0, 6, 7, 8 in Fig 4.1) of extinct ancestors. $f(x_h\vert \theta) = \sum_{x_0} \sum_{x_6} \sum_{x_7} \sum_{x_8} \left[ \pi_{x_0} P_{x_0x_6}(t_6) P_{x_6x_7}(t_7) P_{x_7T}(t_1) P_{x_7C}(t_2) P_{x_6A}(t_3) P_{x_0x_8}(t_8) P_{x_8C}(t_4) P_{x_8C}(t_5) \right]$ (Eq 4.3) where $\pi_{x_0}$ is the prior probability of state $x_0$ at the root (e.g., $1/4$), and $P_{uv}(t)$ is the transition probability from state $u$ to $v$ along a branch of length $t$.

4.2.2 The Pruning Algorithm (Felsenstein, 1973b, 1981)

Efficiently calculates $f(x_h\vert \theta)$ by avoiding redundant computations (variant of dynamic programming).

- Horner’s Rule Principle: Factor out common terms to reduce computations (e.g., sum over $x_7$ before $x_6$, and sum over $x_6, x_8$ before $x_0$ in Eq 4.4).

- Conditional Probability $L_i(x_i)$: Probability of observing data at tips descendant from node $i$, given nucleotide $x_i$ at node $i$.

- If node $i$ is a tip: $L_i(x_i) = 1$ if $x_i$ is the observed nucleotide at that tip, $0$ otherwise.

- If node $i$ is an interior node with daughter nodes $j$ and $k$: $L_i(x_i) = \left[ \sum_{x_j} P_{x_ix_j}(t_j)L_j(x_j) \right] \times \left[ \sum_{x_k} P_{x_ix_k}(t_k)L_k(x_k) \right]$ (Eq 4.5) This calculates the probability of descendant data given $x_i$ by summing over all possible states at daughters $j$ and $k$.

- Traversal: Calculation proceeds from tips towards the root (post-order traversal). Each node is visited only after its descendants.

- Final Likelihood at Root (node 0): $f(x_h\vert \theta) = \sum_{x_0} \pi_{x_0} L_0(x_0)$ (Eq 4.6)

- Example 4.1 (Fig 4.2): Numerical illustration using K80, fixed branch lengths, and $\kappa=2$. Shows calculation of $L_i(x_i)$ vectors up the tree.

- Savings on Computation (4.2.2.2):

- Algorithm scales linearly with number of species (nodes).

- Transition probability matrices $P(t)$ computed once per branch length.

- Identical site patterns: compute likelihood once.

- Partial site patterns (subtrees) can be collapsed if data below them is identical.

- Hadamard Conjugation (4.2.2.3): Alternative method for specific models (e.g., binary characters, Kimura’s 3ST) to transform branch lengths to site pattern probabilities and vice versa. Useful for theoretical analysis on small trees.

4.2.3 Time Reversibility, Root, and Molecular Clock

- Time Reversibility ($\pi_i P_{ij}(t) = \pi_j P_{ji}(t)$): Common in phylogenetic models.

- Pulley Principle (Felsenstein, 1981): The root can be moved arbitrarily along any branch of the tree without changing the likelihood.

- This means for unrooted trees (branches have own rates), only the sum of branches like $t_6+t_8$ in Fig 4.3 is estimable, not $t_6$ and $t_8$ individually. The model is overparameterized.

- Molecular Clock:

- If assumed (single rate, tips equidistant from root), the root can be identified.

- Parameters are ages of ancestral nodes (Fig 4.4a).

- Pulley principle can still simplify calculations (Fig 4.4b, Eq 4.8).

4.2.5 Amino Acid, Codon, and RNA Models

- Pruning algorithm applies directly.

- Difference: State space size (4 for nucleotides, 20 for aa, 61 for codons).

- Likelihood computation is more expensive for aa/codon models.

- RNA dinucleotide models (16 states): For stem regions, model co-evolution of complementary bases. Loop regions can be problematic.

4.2.6 Missing Data, Sequence Errors, and Alignment Gaps

- General Theory (4.2.6.1):

- $X$: observed data (with ambiguities, errors).

- $Y$: unknown true alignment (fully determined).

- $L(\theta, \gamma) = f(X\vert\theta, \gamma) = \sum_Y f(Y\vert\theta) f(X\vert Y, \gamma)$ (Eq 4.9)

- where $\gamma$ are parameters of the error model $f(X\vert Y, \gamma)$.

- Assuming site independence for errors: $L(\theta, \gamma) = \prod_h \left[ \sum_{y_h} f(y_h\vert\theta) f(x_h\vert y_h, \gamma) \right]$ (Eq 4.10)

- Modified Pruning: Set tip vector $L_i(y)$ at tip $i$ with observed state $x_i$ to $f(x_i\vert y_i, \gamma)$ for each true state $y$. In NC-IUB notation, $L_i(y) = \epsilon^{(i)}_{yx_i}$. (Eq 4.11)

- Ambiguities and Missing Data (4.2.6.2): Assuming no sequence errors.

- If $x_i$ is an ambiguous code (e.g., Y for T or C), set $L_i(y)=1$ if $y$ is compatible with $x_i$, and 0 otherwise. (e.g., for Y, $L_i = (1,1,0,0)$). This is the common practice.

- This approach implicitly assumes the probability of observing an ambiguity (e.g., Y) is the same whether the true base was T or C. If not, it’s incorrect.

- Sequence Errors (4.2.6.3): Model error as a $4 \times 4$ transition matrix $E = {\epsilon_{yx}}$ where $\epsilon_{yx}$ is $P(\text{observe } x \vert \text{true } y)$. The tip vector $L_i$ becomes the relevant column of $E$.

- Alignment Gaps (4.2.6.4): Most difficult.

- Models of indels are complex and computationally intensive.

- Ad hoc treatments (for $f(Y\vert\theta)$, ignoring $f(X\vert Y, \gamma)$):

- Treat gap as 5th state: Problematic (treats multi-site indel as multiple events).

- Delete columns with any gaps: Information loss.

- Treat gaps as missing data (N or ?): Problematic (gap means nucleotide doesn’t exist, not that it’s unknown).

- Common practice: Remove unreliable alignment regions, especially for divergent sequences.

4.3 Likelihood Calculation Under More Complex Models

Models assuming all sites evolve at the same rate with the same pattern are unrealistic.

4.3.1 Mixture Models for Variable Rates Among Sites

- 4.3.1.1 Discrete-Rate Model:

- Sites fall into $K$ classes, class $k$ has rate $r_k$ with probability $p_k$.

- Constraints: $\sum p_k = 1$, average rate $\sum p_k r_k = 1$.

- $2(K-1)$ free parameters. Substitution matrix at site is $r_k Q$.

- Likelihood at a site: $f(x_h\vert\theta) = \sum_{k=1}^K p_k \times f(x_h\vert r=r_k; \theta)$ (Eq 4.15) (Calculate likelihood $K$ times, once for each rate category, then average).

- $K$ should not exceed 3 or 4 in practice; parameters hard to interpret.

- Invariant-Site Model (+I): Special case, $K=2$. Rate $r_0=0$ (invariable) with prob $p_0$, rate $r_1=1/(1-p_0)$ with prob $1-p_0$. One parameter $p_0$. (Eq 4.17)

- 4.3.1.2 Gamma-Rate Model (+$\Gamma$):

- Rates drawn from a continuous gamma distribution $g(r; \alpha, \beta)$.

- Set mean $\alpha/\beta = 1$ (so $\alpha=\beta$). One shape parameter $\alpha$.

- Likelihood at a site: $f(x_h\vert \theta) = \int_0^\infty g(r) f(x_h\vert r; \theta) dr$ (Eq 4.19)

- 4.3.1.3 Discrete Gamma Model:

- Approximates continuous gamma with $K$ discrete categories.

- Each category has probability $p_k=1/K$.

- $r_k$ is the mean (or median) rate for the $k^{th}$ quantile of the gamma distribution (Fig 4.9). Only $\alpha$ is a free parameter.

- $K=4$ or $K=5$ often good approximation. Computationally $K$ times slower.

- This is generally preferred over the general discrete-rate model due to fewer, more stable parameters.

- Example 4.3 (12S rRNA): Discrete gamma fits better than general discrete-rate.

- Pathological “I+$\Gamma$” Model (4.3.1.4):

- Proportion $p_0$ of sites are invariable; rest $1-p_0$ have rates from gamma.

- Strong correlation between $p_0$ and $\alpha$, hard to estimate. Sensitive to data. Often selected by automated tools but should be avoided. Simple gamma (+$\Gamma$) is preferred.

- Gamma Mixture Model: Rates from a mixture of two gamma distributions. More stable than I+$\Gamma$.

- Empirical Bayes (EB) Estimation of Site Rates (4.3.1.5):

- After estimating model parameters $\hat{\theta}$ (including $\alpha$ or $p_k, r_k$), estimate rate for a specific site $h$ using its posterior distribution: $f(r\vert x_h; \hat{\theta}) = \frac{f(r\vert \hat{\theta}) f(x_h\vert r; \hat{\theta})}{f(x_h\vert \hat{\theta})}$ (Eq 4.21)

- Posterior mean can be used as the rate estimate.

- Correlated Rates at Adjacent Sites (4.3.1.6): Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) where rate class transition depends on previous site’s class. Rates are correlated. More complex.

- Covarion Models (4.3.1.7):

- A site can switch its evolutionary rate class over time along different lineages. (Fast on one branch, slow on another).

- Expanded state space: e.g., A+, A-, C+, C- (on/off states). If nucleotide is ‘off’, it doesn’t change. If ‘on’, it changes according to a standard model.

- Handled by standard pruning algorithm on the expanded state space.

4.3.2 Mixture Models for Pattern Heterogeneity Among Sites

- Different sites might evolve under different substitution patterns (e.g., different $Q$ matrices, different $\pi$ vectors), not just different overall rates.

- Example: Mixture of several empirical amino acid matrices for different site classes. If matrices are fixed, no new parameters.

4.3.3 Partition Models for Combined Analysis of Multiple Datasets

- If a priori knowledge exists about site heterogeneity (e.g., codon positions, different genes).

- Assign different parameters (rates $r_k$, $\kappa_k$, $\pi_k$, even topology $\tau_k$) to different partitions.

- Log-likelihood is sum over sites, using parameters specific to the partition $I(h)$ of site $h$: $l(\theta, r_1, …, r_K; X) = \sum_h \log{f(x_h\vert r_{I(h)}; \theta)}$ (Eq 4.22)

- Useful for multi-gene datasets, accommodating different evolutionary dynamics per gene/partition.

- Distinction from mixture models: in partition models, site assignment to a partition is known.

- Debate: Combined analysis (supermatrix, with partitions) vs. separate analysis (then supertree). Partitioned likelihood is a form of combined analysis that accounts for heterogeneity.

4.3.4 Nonhomogeneous and Nonstationary Models

- Deal with varying base/amino acid compositions among sequences/lineages (violation of stationarity).

- Branch-Specific Frequencies: Assign different equilibrium frequency vectors ($\pi^{(b)}$) to different branches or parts of the tree. Many parameters.

- GC Content Models: Simpler versions where only GC content varies.

- Computationally difficult. Likelihood calculation requires modifications as $P_{ij}(t)$ depends on $\pi$ at both ends of branch if non-stationary.

- Bayesian methods with priors on frequency drift can be used.

4.4 Reconstruction of Ancestral States (ASR)

Inferring character states at internal nodes of a tree.

4.4.1 Overview

- Traditional uses: comparative method, “chemical paleogenetic restoration” (synthesizing ancestral proteins).

- Parsimony ASR (e.g., Fitch, Sankoff) was common.

- Likelihood/Empirical Bayes (EB) Approach (Yang et al. 1995a): Calculates posterior probabilities of states at ancestral nodes, given data and model parameters (MLEs).

- Accounts for branch lengths, varying rates. Provides uncertainty measure.

4.4.2 Empirical and Hierarchical Bayesian Reconstruction

- Marginal Reconstruction: Posterior probability of state $x_a$ at a single ancestral node $a$.

- To find $P(x_a \vert X, \theta)$: Reroot tree at node $a$. Then $P(x_a \vert X, \theta) = \frac{\pi_{x_a} L_a(x_a)}{\sum_{x’a} \pi{x’_a} L_a(x’_a)}$ (Eq 4.23, where $L_a(x_a)$ is likelihood of data given $x_a$ at new root $a$).

- Example (Fig 4.2): Root at node 0. $P(X_0=C\vert data) = 0.901$.

- Joint Reconstruction: Posterior probability of a set of states for all ancestral nodes simultaneously.

- $P(y_A \vert X, \theta) = \frac{P(X, y_A \vert \theta)}{P(X\vert \theta)}$, where $y_A=(x_0, x_6, …)$ is a specific combination of ancestral states.

- Numerator is $\pi_{x_0} \times \prod P(\text{daughter state} \vert \text{parent state})$ (Eq 4.24).

- Denominator is overall site likelihood $f(X\vert \theta)$.

- Finding the best joint reconstruction often uses dynamic programming (similar to Sankoff’s).

- Marginal probabilities should not be multiplied to get joint probabilities (states at different nodes are not independent).

- Comparison with Parsimony (4.4.2.3): EB and parsimony similar under JC69 + equal branches. Differ with complex models/unequal branches. EB provides probabilities.

- Hierarchical Bayesian ASR (4.4.2.4): Integrates over uncertainty in model parameters (branch lengths, $\kappa$, $\alpha$) by assigning priors and using MCMC. More robust for small datasets.

- Uncertainty in phylogeny is a more complex issue. Often, a fixed (e.g., ML) tree is used.

*4.4.3 Discrete Morphological Characters

- Same EB theory applies.

- Difficulties:

- Few characters, so model parameters (rates $q_{01}, q_{10}$; branch lengths) hard to estimate reliably from the character itself. Using molecular branch lengths is an option but potentially problematic.

- Rate symmetry ($q_{01}=q_{10}$) assumption is critical.

- Equal branch length assumption is highly unrealistic.

- Hierarchical Bayesian approach (averaging over parameter uncertainty) is preferred but sensitive to priors. Classical ML struggles with few data points.

4.4.4 Systematic Biases in Ancestral Reconstruction

- Using only the most probable ancestral state (ignoring suboptimal ones) can lead to biases.

- Example (Fig 4.10): If true ancestral base compositions are skewed (e.g., A more frequent than G), and ASR reconstructs A when data is AAG/AGA/GAA and G for GGA/GAG/AGG, this can lead to an artificial “drift” in reconstructed ancestral compositions if one state is more common in the data.

- Remedy: Instead of using only the “best” reconstruction, use a likelihood approach that sums over all possible ancestral states, weighted by their probabilities. Or, in ASR-based methods, weight contributions from suboptimal reconstructions by their posterior probabilities.

*4.5 Numerical Algorithms for Maximum Likelihood Estimation

Finding MLEs $\hat{\theta}$ by maximizing $l(\theta)$ or minimizing $f(\theta) = -l(\theta)$. Derivatives $\partial l / \partial \theta_i = 0$. Usually requires iterative numerical methods.

*4.5.1 Univariate Optimization (Line Search)

- Golden Section Search (4.5.1.1): Reduces interval of uncertainty for a unimodal function by comparing values at two interior points defined by the golden ratio. Linear convergence. (Fig 4.11, 4.12)

- Newton’s Method (Newton-Raphson) (4.5.1.2): Uses first ($f’$) and second ($f’’$) derivatives. Approximates function locally by a parabola. $\theta_{k+1} = \theta_k - f’(\theta_k) / f’’(\theta_k)$ (Eq 4.30) Quadratic convergence (fast) near minimum if $f’’(\theta_k)>0$. Requires derivatives. Can diverge if far from minimum or $f’’ \approx 0$. Safeguards needed (e.g., step halving, Eq 4.31).

*4.5.2 Multivariate Optimization

(Covered in detail in previous summary from provided image, Section 4.5.2 of text)

- Optimizing one parameter at a time (axis iteration) is inefficient if parameters are correlated (Fig 4.13).

- Standard methods update all variables simultaneously.

- Steepest-Descent (4.5.2.1): Move in direction of negative gradient $-g$. Then line search. Slow zigzagging near minimum if valley is narrow/curved. (Other methods like Newton, Quasi-Newton (BFGS, DFP) are described in the text page 138, which was part of a previous query).

4.5.2.2 Newton’s Method (Multivariate)

- Relies on a quadratic approximation of the objective function $f(\theta)$ around the current point $\theta_k$.

- Uses the gradient vector $g_k$ (first partial derivatives) and the Hessian matrix $G_k$ (second partial derivatives, $G = d^2f(\theta)$).

- Taylor expansion: $f(\theta) \approx f(\theta_k) + g_k^T (\theta - \theta_k) + \frac{1}{2} (\theta - \theta_k)^T G_k (\theta - \theta_k)$ (Eq 4.32)

- Minimizing this quadratic approximation yields the next iterate: $\theta_{k+1} = \theta_k - G_k^{-1} g_k$ (Eq 4.33)

- Drawbacks: Same as univariate Newton’s method (requires first and second derivatives, can diverge if not close to minimum).

- Safeguarded Newton Algorithm:

- Use $s_k = -G_k^{-1} g_k$ as a search direction.

- Perform a line search to find step length $\alpha_k$: $\theta_{k+1} = \theta_k + \alpha_k s_k$ (Eq 4.34)

- Simpler: Try $\alpha_k = 1, 1/2, 1/4, …$ until $f(\theta_{k+1}) \le f(\theta_k)$.

- If $G_k$ is not positive definite (required for minimization), it can be reset (e.g., to identity matrix $I$).

- Information Matrix: When $f(\theta) = -l(\theta)$ (negative log-likelihood), $G_k = -\frac{d^2l}{d\theta^2}$ is the observed information matrix.

- Scoring Method: Uses expected information matrix $I(\theta) = -E\left[\frac{d^2l}{d\theta^2}\right]$ instead of $G_k$ if it’s easier to calculate.

- Benefit: Approximate variance-covariance matrix of MLEs ($G_k^{-1}$ or $I(\hat{\theta})^{-1}$) is available at convergence.

4.5.2.3 Quasi-Newton Methods

- Require first derivatives ($g$) but not second derivatives ($G$).

- Build up an approximation $B_k$ to the inverse Hessian $G_k^{-1}$ iteratively using values of $f$ and $g$.

- Basic Algorithm: a. Initial guess $\theta_0$, initial $B_0$ (e.g., identity matrix). b. For $k = 0, 1, 2, …$ until convergence: 1. Test $\theta_k$ for convergence. 2. Calculate search direction: $s_k = -B_k g_k$. 3. Line search along $s_k$ to find step length $\alpha_k$: $\theta_{k+1} = \theta_k + \alpha_k s_k$. 4. Update $B_k$ to $B_{k+1}$ (using formulae like BFGS or DFP).

- $B_k$ is a symmetric positive definite matrix.

- More efficient than derivative-free methods if first derivatives (even approximated) are available.

4.5.2.4 Bounds and Constraints

- Many phylogenetic parameters have bounds (e.g., branch lengths $t \ge 0$; nucleotide frequencies $\pi_i > 0, \sum \pi_i = 1$; divergence times $t_0 > t_1 > t_2 > t_3$).

- Constrained optimization is complex.

- Variable Transformation: An effective way to convert a constrained problem to an unconstrained one.

- Example (frequencies $\pi_1, \pi_2, \pi_3, \pi_4$): Use unconstrained $x_1, x_2, x_3 \in (-\infty, \infty)$, set $x_4=0$. Let $s = e^{x_1} + e^{x_2} + e^{x_3} + e^{x_4}$ (denominator, using $e^{x_4}=1$). Then $\pi_i = e^{x_i}/s$. This ensures $\pi_i > 0$ and $\sum \pi_i = 1$. (Note: text typo $\pi_1=x_1/s$ is incorrect, it should be $\pi_1=e^{x_1}/s$ or similar for positivity).

- Example (divergence times $t_0 > t_1 > t_2 > t_3 > 0$): Define $x_0 = t_0$ (root age) $x_1 = t_1/t_0$ $x_2 = t_2/t_1$ $x_3 = t_3/t_2$ New constraints: $0 < x_0 < \infty$ (can use $x_0=e^{y_0}$), and $0 < x_1, x_2, x_3 < 1$. The ratio $x_i = t_i / t_{\text{mother node}}$ ensures $0 < x_i < 1$ for non-root nodes if $t_i < t_{\text{mother node}}$.

4.6 ML Optimization in Phylogenetics

4.6.1 Optimization on a Fixed Tree

- Parameters include branch lengths ($t$) and substitution model parameters ($\psi$).

- Direct multivariate optimization is inefficient because changing one branch length $t_b$ only affects conditional likelihoods $L_i(x_i)$ ancestral to that branch.

- Optimize One Branch Length at a Time:

- Keep other branches and $\psi$ fixed.

- For branch $b$ connecting nodes $a$ and $b’$ (with length $t_b$), the likelihood can be written (by temporarily rooting at $a$): $f(x_h\vert \theta) = \sum_{x_a} \sum_{x_{b’}} \pi_{x_a} P_{x_a x_{b’}}(t_b) L_a(x_a) L_{b’}(x_{b’})$ (Eq 4.35, adapted from notation)

- First and second derivatives of $l$ w.r.t $t_b$ can be calculated analytically.

- $t_b$ can be optimized efficiently using Newton’s method.

- Iterate through all branches.

- Optimizing Substitution Parameters ($\psi$):

- A change in $\psi$ typically affects all conditional probabilities.

- Two-Phase Strategy (Yang, 2000b):

- Phase 1: Optimize all branch lengths one-by-one (Newton’s) with $\psi$ fixed. Cycle until convergence.

- Phase 2: Optimize $\psi$ (e.g., BFGS) with branch lengths fixed.

- Repeat 1 & 2.

- Works well if $t$ and $\psi$ are not strongly correlated (e.g., $\kappa$ in HKY85).

- Inefficient if strongly correlated (e.g., branch lengths and $\alpha$ for gamma rates).

- Embedded Strategy (Swofford, 2000):

- Outer loop: Optimize $\psi$ using multivariate algorithm (e.g., BFGS).

- Inner loop: For each set of $\psi$ values proposed by BFGS, re-optimize all branch lengths before calculating the likelihood.

- More robust to correlations but computationally intensive.

4.6.2 Multiple Local Peaks on the Likelihood Surface for a Fixed Tree

- Numerical optimization algorithms are local hill-climbers and may find a local, not global, maximum.

- More common with complex, parameter-rich models or near parameter boundaries (e.g., zero branch lengths).

- Symptom: Different starting values lead to different MLEs and likelihood scores.

- Remedy: No foolproof solution.

- Multiple runs from different initial values.

- Stochastic search algorithms (simulated annealing, genetic algorithms).

4.6.3 Search in the Tree Space

- If tree topology ($\tau$) is unknown, this is a much harder problem.

- Two Levels of Optimization:

- Inner: Optimize parameters (branch lengths, $\psi$) for a fixed $\tau$ to get $l(\hat{\theta}_\tau \vert X)$.

- Outer: Search tree space for $\tau$ that maximizes $l(\hat{\theta}_\tau \vert X)$.

- Example (3 taxa, binary characters, clock - Fig 4.14, 4.15):

- Data: counts $(n_0, n_1, n_2, n_3)$ or frequencies $(f_0, f_1, f_2, f_3)$ of site patterns (xxx, xxy, yxx, xyx).

- Probabilities of site patterns $p_0, p_1, p_2$ (Eq 4.37, note $p_2=p_3$). $P(\text{data}\vert \tau, t_0, t_1)$ is multinomial (Eq 4.36).

- Parameter space for each tree $\tau_i$ forms a triangle within the sample space (tetrahedron).

- MLE for a fixed tree $\tau_i$ corresponds to finding point in its parameter space closest to observed $f_i$ by Kullback-Leibler divergence: $D_{KL}(f \vert \vert p) = \sum_i f_i \log (f_i/p_i)$ (Eq 4.38) Minimizing $D_{KL}$ is equivalent to maximizing $\sum n_i \log p_i$.

- The ML tree is the one whose parameter space is closest to the data.

- Practical Tree Search:

- Uses tree-rearrangement algorithms (NNI, SPR, TBR - see Chapter 3).

- Candidate trees are evaluated; only affected branch lengths are re-optimized for speed.

4.6.4 Approximate Likelihood Method

- Historically, to reduce computation:

- Use other methods (e.g., LS, parsimony) to estimate branch lengths on a given tree, then calculate likelihood.

- Quartet Puzzling: ML for all quartets, then assemble.

- Less important now with faster exact ML programs (e.g., RAxML), but can be useful for initial trees.

4.7 Model Selection and Robustness

This section discusses how to choose appropriate evolutionary models for ML analysis and how to evaluate their fit and the reliability of inferences.

4.7.1 Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) Applied to rbcL Dataset

- LRT Principle: Compares the fit of two nested models.

- $H_0$: Simpler model. $H_1$: More complex model.

- Test statistic: $\Delta = 2(l_1 - l_0)$, where $l_1$ and $l_0$ are maximized log-likelihoods under $H_1$ and $H_0$.

- Under $H_0$, $\Delta \sim \chi^2_{df}$, where $df$ is the difference in the number of free parameters.

- Example (rbcL dataset, Table 4.3, 4.4):

- JC69 vs. K80: $H_0: \kappa=1$. K80 has 1 extra parameter ($\kappa$). $df=1$. $2\Delta l = 296.3$. Critical $\chi^2_{1,1\%} = 6.63$. JC69 is rejected.

- JC69 vs. JC69+$\Gamma_5$ (rate variation): $H_0: \alpha=\infty$ (one rate). Alternative has $\alpha$ (1 extra parameter for gamma shape).

- Boundary Issue: $\alpha=\infty$ is at the boundary of parameter space. The null distribution for $\Delta$ is a 50:50 mixture of a point mass at 0 and a $\chi^2_1$ distribution.

- Using standard $\chi^2_1$ is too conservative.

- For rbcL, $2\Delta l = 648.42$, very significant regardless of the exact null.

- JC69 vs. JC69+C (codon position rates): $H_0: r_1=r_2=r_3$. Alternative allows different rates for 3 codon positions (2 extra parameters). $df=2$. $2\Delta l = 678.50$. JC69 is rejected.

- Typical Pattern: More complex models (e.g., HKY85+$\Gamma_5$, HKY85+C) are often not rejected, while simpler ones are. LRT tends to favor parameter-rich models with large datasets.

4.7.2 Test of Goodness of Fit and Parametric Bootstrap

- Goodness-of-Fit (GoF): Assesses if a single model adequately describes the data (absolute fit), not just relative to a simpler model.

- Saturated Model (Multinomial): Assigns a probability to each of $4^s$ possible site patterns for $s$ sequences. Has $4^s-1$ parameters. Max log-likelihood under this is $l_{max} = \sum_{i=1}^{4^s} n_i \log(n_i/n)$ (Eq 4.39), where $n_i$ is count of pattern $i$.

- Problem: Standard $\chi^2$ GoF test (comparing model $l$ to $l_{max}$) usually not applicable because many site patterns have low/zero counts.

- Parametric Bootstrap for GoF (Goldman 1993a):

- Fit the chosen model (e.g., HKY85+$\Gamma_5$) to real data $\rightarrow \hat{\theta}$. Calculate $l_{model}$ and $l_{max}$. Test statistic $\Delta l_{obs} = l_{max} - l_{model}$.

- Simulate many (e.g., 1000) replicate datasets from the fitted model (Given the tree topology and using $\hat{\theta}$).

- For each simulated dataset, re-calculate $l_{max,sim}$ and $l_{model,sim}$, get $\Delta l_{sim}$.

- The distribution of $\Delta l_{sim}$ values is the null distribution.

- If $\Delta l_{obs}$ is in the extreme tail of this distribution (e.g., p-value = proportion of $\Delta l_{sim} > \Delta l_{obs}$ is small), the model fits poorly.

- Parametric bootstrap is general but computationally expensive.

*4.7.3 Diagnostic Tests to Detect Model Violations

If GoF rejects a model, these help identify which assumptions are violated.

- Number of Distinct Site Patterns (Goldman 1993b): If model ignores rate variation, it might predict too few distinct patterns, too many constant sites, etc., compared to observed data. Use bootstrap to get expected distribution.

- Stationarity of Frequencies: Are base/amino acid frequencies homogeneous across sequences? Test with $s \times 4$ contingency table.

- Symmetry/Reversibility (Tavaré 1986): For two sequences, count of pattern $ij$ ($N_{ij}$) should equal count of $ji$ ($N_{ji}$) if process is reversible. $X^2 = \sum_{i<j} \frac{(N_{ij} - N_{ji})^2}{N_{ij} + N_{ji}}$ (Eq 4.40). Approx $\chi^2_6$ for nucleotides. Powerful for detecting small violations.

4.7.4 Akaike Information Criterion (AIC and AICc)

- Compares models (nested or non-nested). Penalizes for number of parameters ($p$).

- AIC (Akaike 1974): $AIC = -2l + 2p$ (Eq 4.41). Prefer model with lower AIC. Extra parameter “worth it” if it improves $l$ by >1.

- Perceived to not penalize complex models enough.

- AICc (Corrected AIC, Sugiura 1978): Includes sample size $n$ (sequence length). $AICc = -2l + \frac{2np}{n-p-1} = AIC + \frac{2p(p+1)}{n-p-1}$ (Eq 4.42) Recommended over AIC, especially for smaller $n$.

4.7.5 Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)

- BIC (Schwarz 1978): $BIC = -2l + p \log(n)$ (Eq 4.43).

- Penalizes parameters more harshly than AIC for $n > 8$ (since $\log n > 2$). Tends to favor simpler models, especially with large datasets.

- All (LRT, AIC, BIC) are formulations of Occam’s Razor.

- MODELTEST (Posada & Crandall 1998): Automates model selection using these criteria. Caution: Mechanical application can lead to overly complex (e.g., pathological I+$\Gamma$) models.

4.7.6 Model Adequacy and Robustness

- Quote: “All models are wrong but some are useful.” (George Box)

- Purpose of Model:

- If model is the hypothesis (e.g., testing molecular clock).

- If model is a nuisance (needed for inference, e.g., substitution model for tree reconstruction). This section focuses on selecting nuisance models.

- Model Fit vs. Impact on Inference:

- Adequacy: How well the model statistically fits the data.

- Robustness: How much the inference (e.g., tree topology) is affected by model violations.

- Goal of Model Selection: Not to find the “true” model (impossible), but one with sufficient parameters to capture key features of the data relevant to the question asked.

- i.i.d. Models: Most phylogenetic models (even with rate variation like +$\Gamma$, or covarion models) assume sites are independent and identically drawn from some overall (potentially complex) distribution of evolutionary processes. This is a statistical device to reduce parameters.

- Some features are critical for fit AND inference (e.g., variable rates among sites).

- Some features improve fit but have little impact on inference (e.g., Ts/Tv ratio differences between HKY85 and GTR might not change tree much).

- Most troublesome: factors with little impact on fit but HUGE impact on inference (e.g., different models for lineage rates in divergence time estimation can give similar likelihoods but very different times).

- Robustness to Model Choice: ML is generally quite robust to substitution model details, but performance is highly dependent on tree shape (relative branch lengths).

- “Easy” trees (long internal branches): most methods/models work. Wrong simple models might even seem to perform better.

- “Hard” trees (short internal, long external branches): require complex, realistic models to avoid inconsistency (e.g., LBA).

5. Comparison of phylogenetic methods and tests on trees

This chapter discusses the evaluation of statistical properties of tree reconstruction methods and tests for the significance of estimated phylogenies.

5.1 Statistical Performance of Tree Reconstruction Methods

This section outlines criteria for assessing tree reconstruction methods and summarizes findings from simulation studies.

5.1.1 Criteria

When comparing phylogenetic methods, two types of error are distinguished:

- Random Errors (Sampling Errors): Due to the finite length of sequences (sample size $n$). These decrease as $n \to \infty$.

- Systematic Errors: Due to incorrect model assumptions or method deficiencies. These persist or worsen as $n \to \infty$.

Criteria for judging methods include:

- Computational Speed: Distance methods are generally fastest, followed by parsimony, then likelihood/Bayesian methods.

- Statistical Properties:

- 5.1.1.1 Identifiability: A model is unidentifiable if two different parameter sets ($\theta_1, \theta_2$) produce the exact same probability of the data ($f(X\vert \theta_1) = f(X\vert \theta_2)$) for all possible data $X$. In such cases, the parameters cannot be distinguished.

- Example: For a pair of sequences under a time-reversible model like JC69, one cannot separately estimate divergence time $t$ and substitution rate $r$; only their product, the distance $d = t \cdot r$, is identifiable.

- Unidentifiable models should be avoided as they usually indicate flaws in model formulation.

- 5.1.1.2 Consistency: An estimator $\hat{\theta}$ is consistent if it converges to the true parameter value $\theta$ as the sample size $n \to \infty$.

- Formally: $\lim_{n\to\infty} P(\vert \hat{\theta} - \theta\vert < \epsilon) = 1$ for any small $\epsilon > 0$. (Eq 5.1)

- Strong Consistency: $\lim_{n\to\infty} P(\hat{\theta} = \theta) = 1$. (Eq 5.2)

- For phylogenetic trees (not regular parameters), a method is consistent if the probability of estimating the true tree approaches 1 as $n \to \infty$. This assumes the correctness of the model for model-based methods.

- Parsimony can be inconsistent (Felsenstein 1978b).

- Consistency is considered a fundamental property for any sensible estimator.

- 5.1.1.3 Efficiency: A consistent estimator is efficient if it has the asymptotically smallest variance.

- The variance of a consistent, unbiased estimator $\hat{\theta}$ is bounded by the Cramér-Rao lower bound: $\text{var}(\hat{\theta}) \ge 1/I$, where $I = -E\left[\frac{d^2\log f(X\vert \theta)}{d\theta^2}\right]$ is the Fisher information. (Eq 5.3)

- MLEs are asymptotically consistent, unbiased, normally distributed, and attain this bound.

- Relative Efficiency of Tree Reconstruction Methods:

- $E_{21} = n_1(P)/n_2(P)$: Ratio of sample sizes needed by method 1 ($n_1$) and method 2 ($n_2$) to recover the true tree with the same probability $P$. (Eq 5.4)

- Alternatively: $E^{\ast}{21} = \frac{1 - P{1}(n)}{1 - P_{2}(n)}$: Ratio of error rates for a given sample size $n$. Method 2 is more efficient if $E^*_{21} > 1$. (Eq 5.5)

- 5.1.1.4 Robustness: A model-based method is robust if it performs well even when its assumptions are slightly violated.

- 5.1.1.1 Identifiability: A model is unidentifiable if two different parameter sets ($\theta_1, \theta_2$) produce the exact same probability of the data ($f(X\vert \theta_1) = f(X\vert \theta_2)$) for all possible data $X$. In such cases, the parameters cannot be distinguished.

5.1.2 Performance

Methods for evaluating tree reconstruction performance:

- Laboratory-Generated Phylogenies: True phylogeny is known by experimental design (e.g., Hillis et al., 1992, evolving bacteriophage T7).

- Well-Established Phylogenies: Using phylogenies widely accepted from other evidence (fossils, morphology, previous molecular data).

- Computer Simulation: Generate replicate datasets under a known model and tree, then analyze with different methods. Allows control over parameters.

- Criticisms: Models may be too simple; limited parameter space can be explored.

Generally Accepted Observations from Simulations:

- Clock-assuming methods (e.g., UPGMA) perform poorly if the clock is violated.

- Parsimony and methods using simplistic models are prone to long-branch attraction (LBA). Likelihood with complex models is more robust.

- Likelihood methods are often more efficient than parsimony or distance methods (but see counter-examples).

- Distance methods perform poorly with highly divergent sequences or many gaps.

- Optimal performance is at intermediate levels of sequence divergence.

- Tree shape (relative branch lengths) greatly impacts performance.

- “Hard” trees (short internal, scattered long external branches) are difficult.

- “Easy” trees (long internal branches) are easier. Simplistic models might even outperform complex ones on easy trees.

5.2 Likelihood

Focuses on statistical properties of the ML method for tree reconstruction.

5.2.1 Contrast with Conventional Parameter Estimation

- Tree reconstruction is argued to be a model selection problem, not just parameter estimation.

- Each tree topology $\tau$ represents a different statistical model $f_k(X\vert \theta_k)$, where $\theta_k$ are parameters (branch lengths, substitution model parameters) specific to that topology.

- The likelihood function itself changes with the topology.

5.2.2 Consistency

- ML is consistent for tree reconstruction if the model is correct and identifiable.

- Proof Idea: As sequence length $n \to \infty$:

- Observed site pattern frequencies $f_i$ approach true probabilities $p_i^{(1)}(\theta^{(1)})$ predicted by the true tree ($\tau_1$) and true parameters ($\theta^{(1)}$).

- The MLEs of parameters on the true tree $\hat{\theta}^{(1)}$ approach $\theta^{(1)*}$.

- The maximized log-likelihood for the true tree $l_1 = n \sum f_i \log \hat{p}i^{(1)}(\hat{\theta}^{(1)})$ approaches the maximum possible log-likelihood $l{max} = n \sum f_i \log f_i$. (Eq 5.6, 5.7)

- For any wrong tree $\tau_k$, $l_k$ will be less than $l_{max}$ because its predicted probabilities $\hat{p}_i^{(k)}(\hat{\theta}^{(k)})$ cannot perfectly match all $f_i$.

- The difference $(l_{max} - l_k)/n = \sum f_i \log (f_i / \hat{p}_i^{(k)}(\hat{\theta}^{(k)}))$ is the Kullback-Leibler (K-L) divergence, which is positive if the distributions differ. (Eq 5.8)

- The question of whether a wrong tree can perfectly mimic the true tree (unidentifiability) is crucial. Models commonly used in phylogenetics are generally identifiable.

5.2.3 Efficiency

- Counterintuitive Results: Simulation studies showed that ML under the true model can sometimes have a lower probability of recovering the true tree than parsimony or ML under a wrong/simpler model.

- This is not necessarily due to small sample sizes; the effect can persist as $n \to \infty$.

- Fig 5.1: Shows ML with a false model (JC69, $\alpha=\infty$) outperforming ML with the true model (JC69+$\Gamma$, $\alpha=0.2$) for certain tree shapes. The relative efficiency $E^*_{TF} = (1-P_F)/(1-P_T)$ can be < 1.

- Explanation (Swofford et al. 2001; Bruno & Halpern 1999):

- Parsimony or ML under a simple/wrong model might have an inherent “bias” (e.g., parsimony’s tendency to group long branches).

- If the true tree happens to have a shape that aligns with this bias (e.g., Farris zone in Fig 5.2), the biased method might recover it more readily than ML under the true model, which evaluates evidence “correctly” but might be “slower” to converge to the truth in these specific zones.

- Conclusion: ML for tree reconstruction is not asymptotically efficient in the conventional sense (unlike MLEs for regular parameters). There exist regions of parameter space ($\aleph$) where other methods may be asymptotically more efficient.

- This does not endorse using wrong models for real data analysis. ML under the true (or best approximating) model is always consistent, while parsimony or ML under wrong models can be inconsistent.

5.2.4 Robustness

- ML is generally highly robust to violations of model assumptions.

- More robust to rate variation among sites than distance methods like NJ, if rate variation is modeled (e.g., +$\Gamma$).

- Ignoring significant rate variation can make ML inconsistent.

- Heterotachy: (Rates for sites changing differently across lineages).

- Standard ML (assuming one set of branch lengths for all sites, i.e., a homogeneous model) can perform worse than parsimony if data is a mixture from different underlying trees/branch length sets (Kolaczkowski & Thornton 2004; Fig 5.3).

- Modeling heterotachy (e.g., mixture models with different branch length sets) makes ML perform well but is complex.

5.3 Parsimony

This section discusses attempts to establish an equivalence between parsimony and likelihood under specific models and arguments for justifying parsimony.

5.3.1 Equivalence with Misbehaved Likelihood Models

- Equivalence Goal: Find a likelihood model under which the Most Parsimonious (MP) tree and the ML tree are identical for every possible dataset.

- Early attempts established equivalence with “pathological” likelihood models, which are statistically problematic (e.g., number of parameters increases with sample size).