Book notes: The Scientist’s Guide to Writing

Last modified: Post views:The Scientist’s Guide to Writing by Stephen B. Heard.

Preface

A good scientist has to be a professional writer.

Part I. What Writing Is

First, most scientific writers aren’t born geniuses,but develop facility with writing by deliberately practicing the craft. Second,the goal of all scientific writing is clarity: effortless transfer of information or argument from writer to reader. Third, it’s enormously helpful for writers to think consciously about their own writing behavior.

1. On Bacon, Hobbes, and Newton, and the Selfishness of Writing Well

“perfection of the sciences is to be looked for notfrom the swiftness or ability of any one inquirer, but from a succession.”

– Francis Bacon in his 1609 essay De Sapientia Veterum

“I distinguish the most commonnotions by accurate definition, for the avoiding of confusion and obscurity”

– Thomas Hobbes, who wrote in the preface to his 1655 work De Corpore

Newton had originally written De mundi systemate in plain language to be accessible to readers (Westfall 1980, 459)but changed his mind and rewrote it as series of propositions, derivations,lemmas, and proofs comprehensible only to accomplished mathematicians. He left little doubt of his intent, telling his friend William Derham that “in order to avoid being baited by little smatterers in mathematics, he [Newton]designedly made his Principia abstruse” (Derham 1733). That is, he wrote to impede communication with other scientists, not to facilitate it!

In the 1680s, Newton had the luxury of writing a difficult book and knowing that every mathematician, physicist, and astronomer who mattered would invest whatever time was needed to grapple with his text. There just weren’t many works of similar importance competing for their attention. But in our modern era, the deluge of published scientific work becomes greater every year.

Newton clung to a world in which the selfish act was to write opaquely, but in the modern world, scientists can do themselves no bigger favor than writing well.

Writing should be Telepathy.

2. Genius, Craft, and What This Book Is About

This book outlines a strategy for you, the ordinary scientific writer practicing your craft—a strategy with two elements. This can be applied through the entire process of scientific writing, from conceiving of a paper through revision and publication.

-

The first element is a relentless focus on the goal of crystal-clear communication: nearly every decision you make should be made with that in mind. Should you include a detail of methodology, or leave it out? Should you write in the active voice or the passive? How many decimal places should you give for the numbers in a table? Should your data be in a table at all, or in a figure? In each case, the route to an answer is the same: the better choice is the one that lets the reader more effortlessly understand the story you have to tell.

-

The second element is deliberate attention not just to what you write, but also to how you write. Many new scientific writers simply sit down and expect writing to happen (finding the process mysterious, as I did, if they think about it at all). Such writers can profit by consciously considering their own practices and behavior as they write. Engaging with yourself this way will let you write more, write more easily, and write better—although it does require honest discussion (even confrontation) with yourself about how you write.

Part II. Behavior

3. Reading

Chapter Summary:

- Reading is a useful way to build writing skills.

- While reading, make notes about writing you find successful or unsuccessful, to model or avoid yourself.

- When modeling your own work after good writing, be careful to avoid plagiarism.

4. Managing Your Writing Behavior

Chapter Summary:

- Understanding and managing your own writing behavior is essential to productive writing. Each writer will have a unique set of behavioral challenges.

- People who are consciously aware of their own behavior are better able to manage it. Tools for maintaining behavioral awareness include posted reminders, writing logs, and monitoring agreements with friends or colleagues.

5. Getting Started

Chapter Summary:

- Many writers struggle with beginning a new project, or even a newday’s writing session.

- Reluctance to start can be unintentional (procrastination) or intentional (believing oneself not yet ready to write).

- Procrastination can be managed with some attention to its psychology, and by manipulating expectancy, value, discounting, and delay.

- Writing can begin before all data and analyses are in hand, and even before you know what your paper will say.

- “Early writing” (writing throughout project design and execution) avoid struggles with starting, makes writing easier, and lets writing help you discover ways to improve the science you’re executing.

6. Momentum

Chapter Summary:

- A career in science requires a substantial and sustained pace of writing.

- Techniques for sustaining discipline at writing include quotas, scheduling, writing at productive times, setting up a distraction-free writing environment, and many other “commitment devices.”

- “Binge” and “snack” writing can each be unhelpful if used exclusively. However, frequent short writing sessions can be surprisingly productive.

- For most writers, “swooping” (rapid production of a first draft, even one of low quality) is far better than “bashing” (revising and polishing as you write).

- Most writers experience “writer’s block.” Effective ways to overcome it involve deliberate changes to writing behavior, but only temporary interruptions in writing.

Part III. Content and Structure

7. Finding and Telling Your Story

A story summary consists of answers to the following nine queries about your work and your story:

- What is the central question?

- Why is this question important?

- What data are needed to answer this question?

- What methods are used to get those data?

- What analysis must be applied for the data to answer the central question?

- What data were obtained?

- What were the results of the analyses?

- How did the analyses answer the central question?

- What does this answer tell us about the broader field? Queries 1–3 and 8–9 should be answered with a single sentence each. Answers 1–3 for your Introduction; 4–5 for your Methods; 6–7 for yourResults, and 8–9 for your Discussion.

Effective ways to sell a story:

- “There’s a controversy in the literature over issue X, and I present the kind of data needed to resolve it.”

- “The fact that we don’t know X hinders our efforts to understand issue Y, which is central to a developing subdiscipline.”

- “Our lack of understanding of thing X impedes our efforts to solve economic problem Y.”

- “We need to know more about thing X because it’s a model system widely used to investigate problems in field Y.”

- “I have discovered thing X, which suggests a way to make progress toward difficult-to-reach goal Y.”

Chapter Summary:

- A paper has a story, with “characters” and a “plot,” and it raises and answers an interesting question.

- Tools for finding and planning your story include the two-sentence mini-summary, wordstacks, concept maps, figure shuffling, and outlining. Outlines may be story summaries, subhead outlines, or topic-sentence outlines.

- Telling your story isn’t enough; you must sell it, too. This means showing how your work solves a problem, or answers a question, that matters to readers.

8. The Canonical Structure of the Scientific Paper

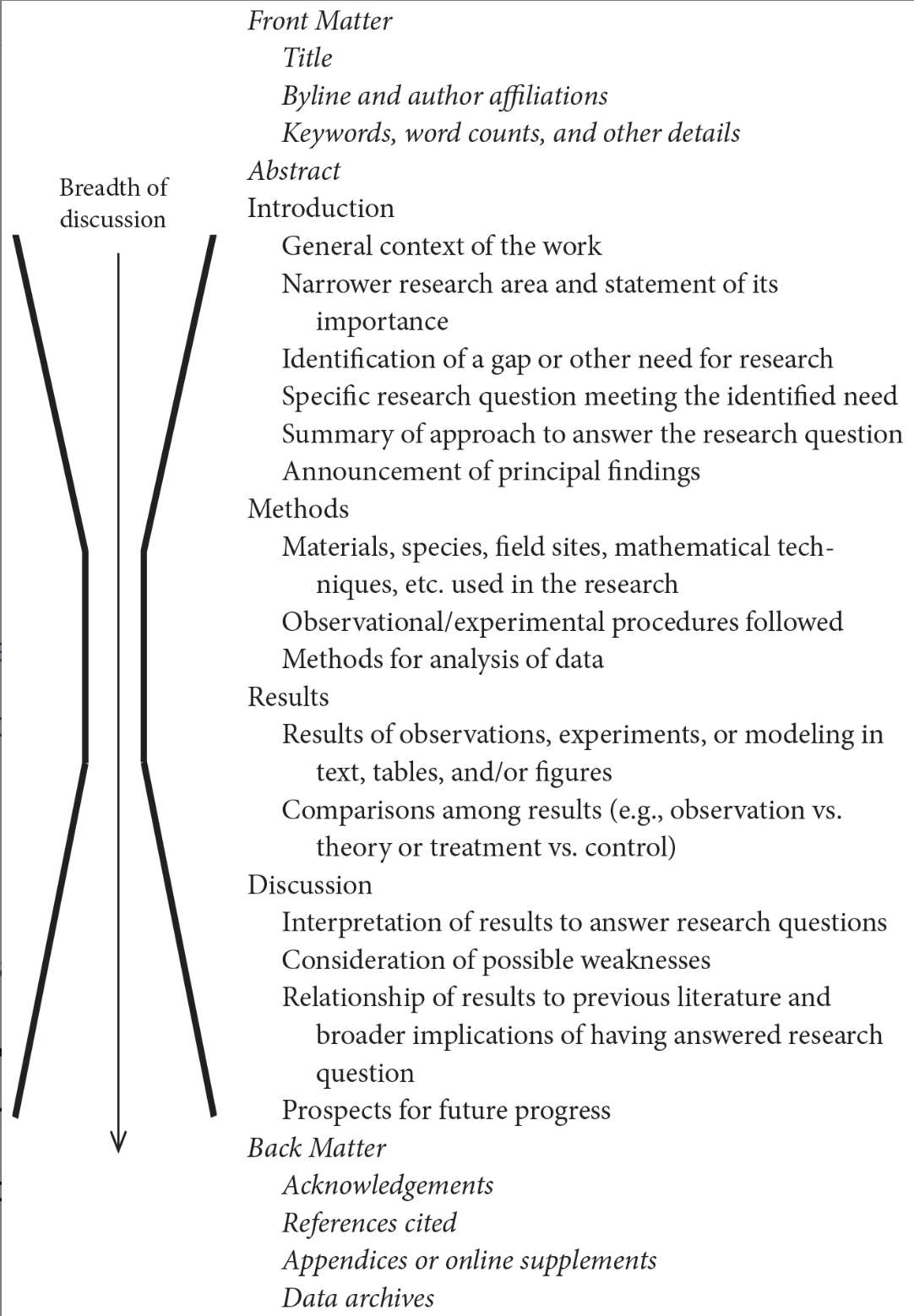

Canonical structure of the modern scientific paper

Chapter Summary:

- The IMRaD structure is now standard for most scientific papers, and includes Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion

- IMRaD functions as a “finding system” for readers, allowing efficient access to content.

- A well-organized paper will have an “hourglass” structure, with focus broad at the beginning, narrowing through the Introduction, and widening again through the Discussion.

9. Front Matter and Abstract

Stronger titles put themselves out there, giving a prospective reader a clear indication of the paper’s story and even suggesting its importance. For instance:

- Protostar distribution and the formation of massive new stars: testing the cluster-assist model

- Can patterns of protostar distribution within molecular clouds distinguish between competing models of massive star formation?

- Detailed images of protostar neighborhoods do not support the cluster-assist model of massive star formation

Chapter Summary:

- A paper’s title is an advertisement, and should indicate the paper’s story.

- The way you list your name in your papers’ bylines should be as consistent as possible throughout your career.

- The Abstract is a short summary of the paper, including question,importance, methods, major results, and conclusions.

10. The Introduction Section

The Introduction combines three functions: advertising, summarizing, and context-setting. Of these, the advertising and summarizing functions have been reduced in importance but not entirely displaced by the addition of the Abstract to the canon. Setting context for the work is now the most important work of the Introduction.

Chapter Summary

- The Introduction serves to define a research territory (context), to establish a niche within that territory (knowledge gap), and to occupy the niche (outlining your approach to filling the knowledge gap).

- Establishing context means a broad focus; exactly how broad depends on the target journal.

- A brief statement of your major result is a strong way to end an Introduction.

11. The Methods Section

Tags: Academic writing

Categories: Book notes

Comments