Paper digest: Modelling pathogens with many strains

Last modified: Post views:How to model pathogens with many strains? Particularly what are the appropriate model settings. Here I revisit two papers on this topic. They are:

- Makau, Dennis N., et al. “Ecological and evolutionary dynamics of multi-strain RNA viruses.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 6.10 (2022): 1414-1422.

- Kucharski, Adam J., Viggo Andreasen, and Julia R. Gog. “Capturing the dynamics of pathogens with many strains.” Journal of mathematical biology 72 (2016): 1-24.

Ecological and evolutionary dynamics of multi-strain RNA viruses

In this Review, we describe multi-strain dynamics from ecological and evolutionary perspectives, outline scales in which multi-strain dynamics occur and summarize important immunological, phylogenetic and mathematical modelling approaches used to quantify interactions among strains.

Ecological versus evolutionary dynamics

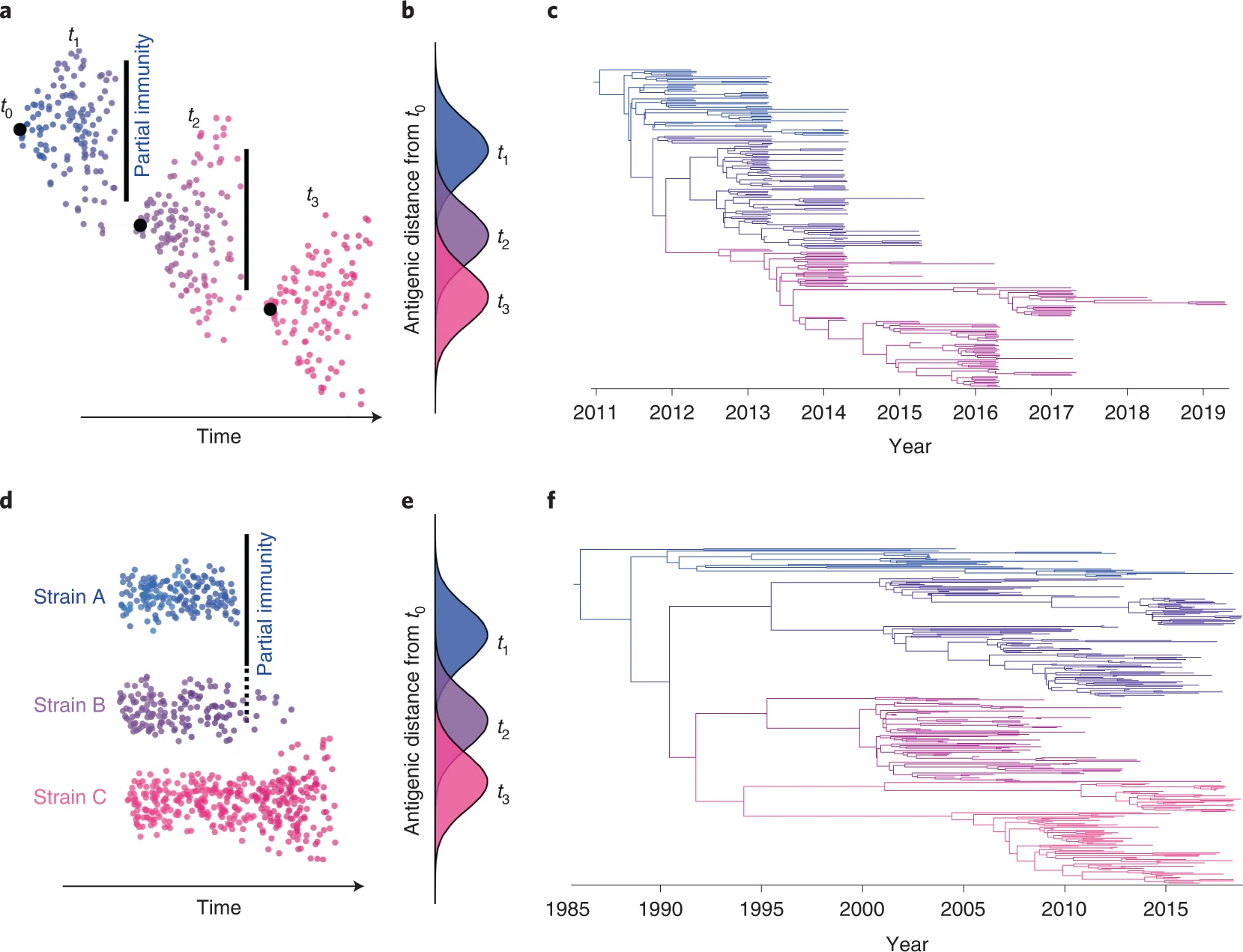

- Ecological multi-strain dynamics: a discrete number of antigenic alternatives or strains exist in the population and strains are assumed not to evolve phenotypically (only neutral or nearly neutral evolution occurs on the timescale of interest). Probably exhibit more symmetrical/balanced phylogenetic trees with longer branches.

- Evolutionary multi-strain dynamics: focusing on how competition and natural selection among genetic variants can drive genetic change, allowing for the emergence of new genetic variants or strains through time. ‘Immune escape’ occurs when a novel antigenic variant evolves that is no longer controlled by individual/herd-level immunity. Often exhibit ladder-like phylogenetic trees wherein older strains go extinct and are replaced by newer strains.

Scales of action and impact of multi-strain dynamics

We can consider multi-strain dynamics at different scales, including the within-host, between-host, and between-population scales.

Quantifying immunogenic interactions between strains

Partial immunity among genetically/immunogenically similar strains can shape the fitness of different strains and influence the likelihood that multiple strains co-circulate in a population.

To quantify antigenic distance between strains, binding and cross-neutralization assays are often used to measure the cross-reactivity of immune reactions elicited by different strains. Antigenic cartography, a computational technique used for graphical visualization of antigenic distances obtained from inhibition assays, can be used to visualize the genetic and antigenic differences among co-circulating variants and identify clusters of variants with similar immune profiles.

Evolutionary processes of multi-strain pathogens

Phylogenetic branching patterns can be analysed to provide insights on multi-strain dynamics and immune-mediated selection, e.g., different phylogenetic patterns (tree shapes) can be observed in Fig 1.

Selection pressures and resulting mutations responsible for adaptation or immune evasion are not always easily identifiable from phylogenetic trees alone. Therefore, we describe four approaches that can complement phylodynamic models to evaluate rates of viral evolution depicted on phylogenetic trees:

- Tajima’s D statistic

- local branching index

- The fixation index (FST)

- dN/dS ratio

Mathematical models of multi-strain pathogens

Multi-strain disease models can track either individuals (agent-based models) or changing proportions of different infection states (compartmental models), but the underlying dynamics are similar: individuals/groups of the population are divided into a finite set of possible classes on the basis of their exposure history.

Challenges:

- Proper number ans resolution of strains

- Cross-immunity (degree, duration, and implementation)

- The incorporation of evolution into models (current practices include (i) allowing epidemiological parameter values to evolve (for example, transmissibility) or (ii) to adding a new parameter corresponding to an abstract phenotype or genotype space)

Population structure and stochasticity

The spreading success of a strain may be more related to host behavioural or physiological attributes than to the fitness of that particular viral strain.

Outstanding questions

Numerous unresolved questions need to be addressed to understand multi-strain dynamics in different host–virus systems.

- (Different scales of multi-strain dynamics) With complex host immune responses and interaction with co-circulating strains, how do co-infection and co-evolution influence the effectiveness of disease management such as vaccination or other control strategies?

- (Different models) Although we have described different phylodynamic tools useful for understanding genetic evolution of co-circulating strains, what are the best approaches to investigate and contextualize antigenic evolution in those strains? In addition, are there distinct and measurable phylogenetic tree topologies characteristic of ecological multi-strain dynamics, and how do perturbations in host populations affect tree structure?

- (Host genetic influence) Host genotypes may non-uniformly influence susceptibility to certain pathogens. How do these host differences affect multi-strain pathogen dynamics at the population level?

- (Host population structure) Host populations may be stratified or substructured for many reasons (natural or artificial). Since strains theoretically evolve to balance transmissibility–virulence trade-offs specific to a given subpopulation, how do changes in host population structure affect the co-evolution/co-circulation of different strains in a population?

- (How to predict) How quickly and to what extent does the fitness of a particular strain vary between individual hosts and across space and time? What are the most suitable approaches to quantify and predict the role of viral fitness in the establishment of multiple strains in a population or subpopulation? Can these tools be used to predict future success or invasion potential of different strains?

Capturing the dynamics of pathogens with many strains

This is also a review article: We provide a comprehensive outline of the benefits and disadvantages of available frameworks, and describe what biological information is preserved and lost under different modelling assumptions. We also consider the emergence of new disease strains, and discuss how models of pathogens with multiple strains could be developed further in future.

Introduction

Many human pathogens can be categorized into distinct strains, each defined by its antigenic properties. This results in a highly complex system, with pathogens interacting through the partial cross-immunity they generate in the host population. Examining the effect of this interaction on disease outbreaks has therefore posed a major challenge, both theoretically and biologically.

Multiple-strain models

One of the most detailed—and computationally intensive — of these frameworks is the individual-based model, which tracks the infection history of every host, updating individuals’ immune status as the disease spreads and evolves during a simulation. Alternatively, population models, in which individuals are grouped into compartments, provide a way of exploring disease dynamics that is analytically tractable as well as easier to implement numerically.

History-based models

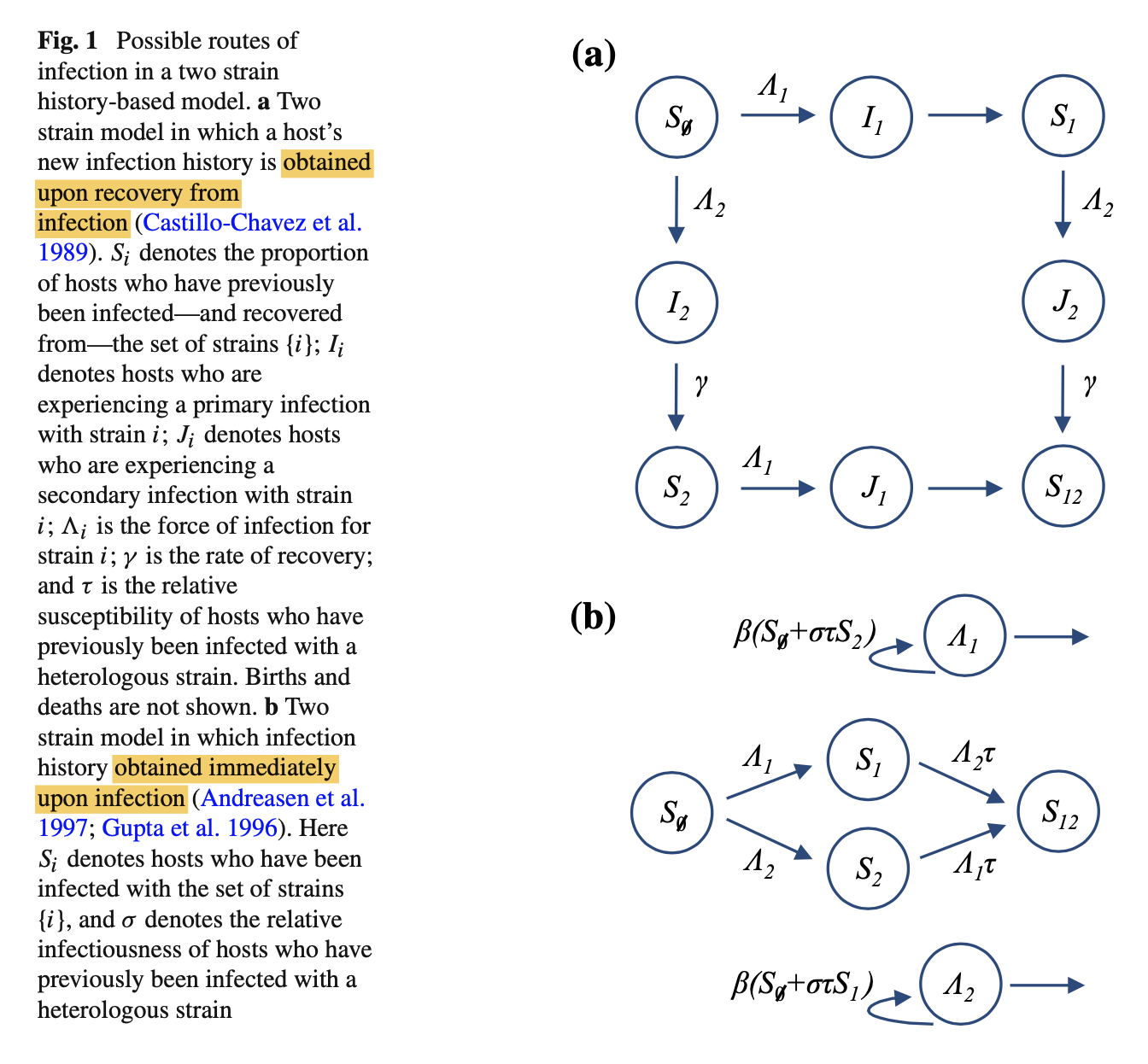

Two strain model

The history-based model is an extension of the SIR model. It has one compartment for each possible combination of prior infection, with cross-immunity dependent on an individual’s infection history.

Cross-immunity can be assumed to act in one of — at least — two ways: either the host is either less likely to be infected by the second strain (‘reduced susceptibility’), or the host will be less likely to transmit the second strain (‘reduced transmission’).

Let $\tau$ denote reduced susceptibility, specifically the relative susceptibility of individuals that have already been infected with one strain. This means the rate at which individuals leave the $S_1$ compartment owing to infection with strain 2 is $\Lambda_2\tau S_1$, where $\Lambda_2$ is the force of infection for strain 2. Next, let $\sigma$ be the relative infectiousness of hosts who have previously been infected with the other strain. We define $\beta_i$ to be the rate of transmission for a primary infection with strain i. Therefore $\Lambda_2 = \beta_2(I_2+\sigma J_2)$.

As additional strains are added, the complexity of this model increases substantially. For n strains, the model has $(n + 2)^{2n−1}$ variables. To simplify the model, we can assume that individuals obtain an updated infection history immediately upon infection (i.e. $μ/γ$ is small).

In Fig 1b, Note that we do not need to keep track of individuals who have left $\hat{I_{i}}$, as they are already included in one of the $S_i$ compartments.

Extension to multiple strains

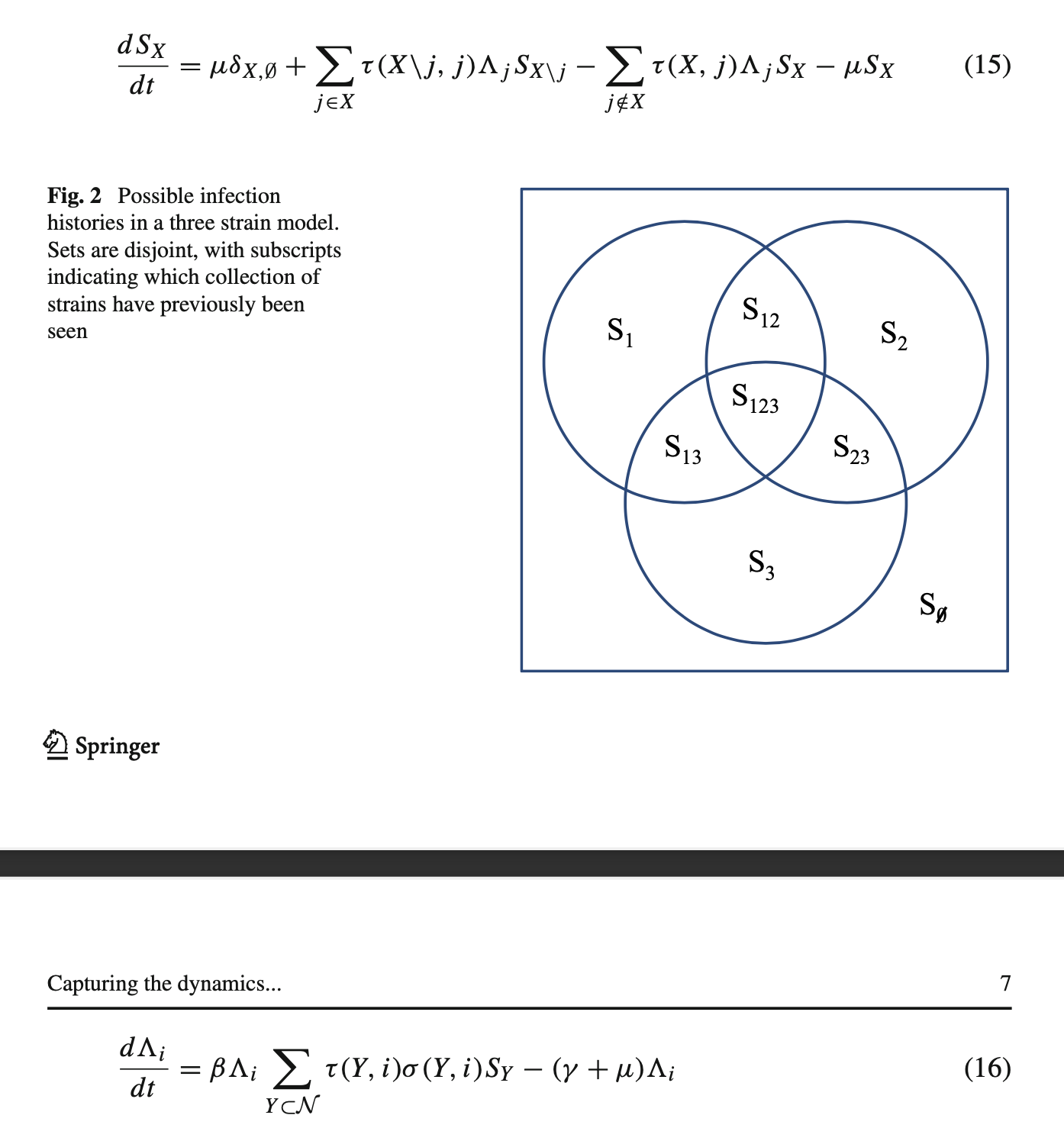

For $n$ disease strains, we define $\mathcal{N} = {1,…,n}$ to be the set of all strains, and let $X$ be some subset of $\mathcal{N}$. There are $2^n$ subsets of $\mathcal{N}$, each representing a different infection history (including the empty set $\empty$ for totally naive individuals). The possible subsets for a three strain model are shown in Fig. 2.

As specified before in Fig. 1b, we obtain the following set of equations (Ferguson and Andreasen 2002):

Model dimension

The drawback with history-based models is the sheer number of possible variables that the system generates: given n strains, there are $2^n$ combinations of infection an individual could have seen.

Model reduction via symmetry

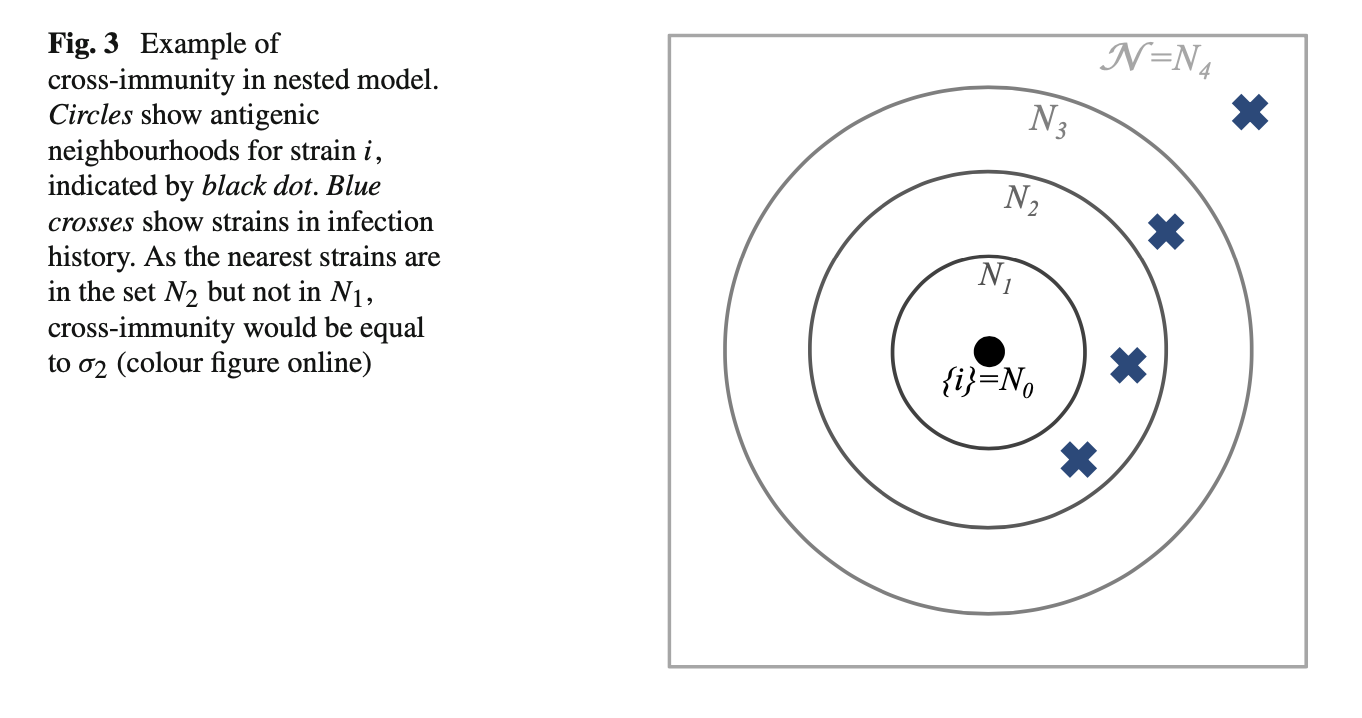

We assume cross-immunity between strains — as measured by antigenic similarity — is consistent with a space in which a given set of strains can be organized into antigenic ‘neighbourhoods’ (Ferguson and Andreasen 2002).

Model reduction via age structure

Another way to group strains into overlapping sets, but the the system will become intractable, one solution is to introduce an age structure into the model.

If immunity acts only to reduce transmission, one might naively expect the probability of having been infected with any two particular strains to be independent: infection with the first strain will not change the rate at which hosts become infected with the second, just the rate at which they transmit. Hence in a two-strain model, might expect $S_{12} = S_1 S_2$. However, if we know a randomly chosen host has previously been infected with the first strain some point in their life, it means they are more likely to be old than young. Hence they are more likely to have also experienced another specific event in the past, such as infection with the second strain. This means $S_{12} ≥ S_1S_2$. The problem can be resolved using the same age-structured logic; if we focus on a specific age group, independence is maintained.

The introduction of age dependency increases model complexity, requiring a system of PDEs rather than ODEs, making it challenging to obtain analytic results, and the requirement that infection with each strain is independent for a specific age group also limits the type of population structure that can be imposed.

Status-based models

The full individual-based model records both the infection history and current immune status of each host. However, there may not be a straightforward relationship between the two: for influenza, infections may not always produce an immune response, and immunity to a certain strain could potentially be generated by one of several past infections (Potter 1979). In principle, it should be possible to develop a compartmental model that accounted for both infection history and immune status. However, in practice the number of possible combinations of infection history and immune status — and hence compartments required — would likely result a model more complex than even a full individual-based framework. To ensure analytical and computational tractability, history-based models therefore capture the individual infection histories in a population, but not the immune statuses; status-based models (Gog and Swinton 2002) do the opposite, recording the current immune status of individuals in the population, but not the combination of past infections that generated that immunity.

The status-based model allows a assumption that upon infection some individuals become completely immune, while the rest remain susceptible. As opposed to the assumption in the history-based model, that individuals with the same infection history will respond to subsequent infection in an identical way: if the set of strains $Y$ have been previously seen, they will transmit strain i with probability $σ (Y, i)$.

Important definitions in a status-based model: Define $C(Y, X, j)$ to be the probability an individual who previously had immunity to a set of strains $Y$ gains immunity against the set of strains $X$ upon infection with strain $j$.

Comparison of models

Model structure

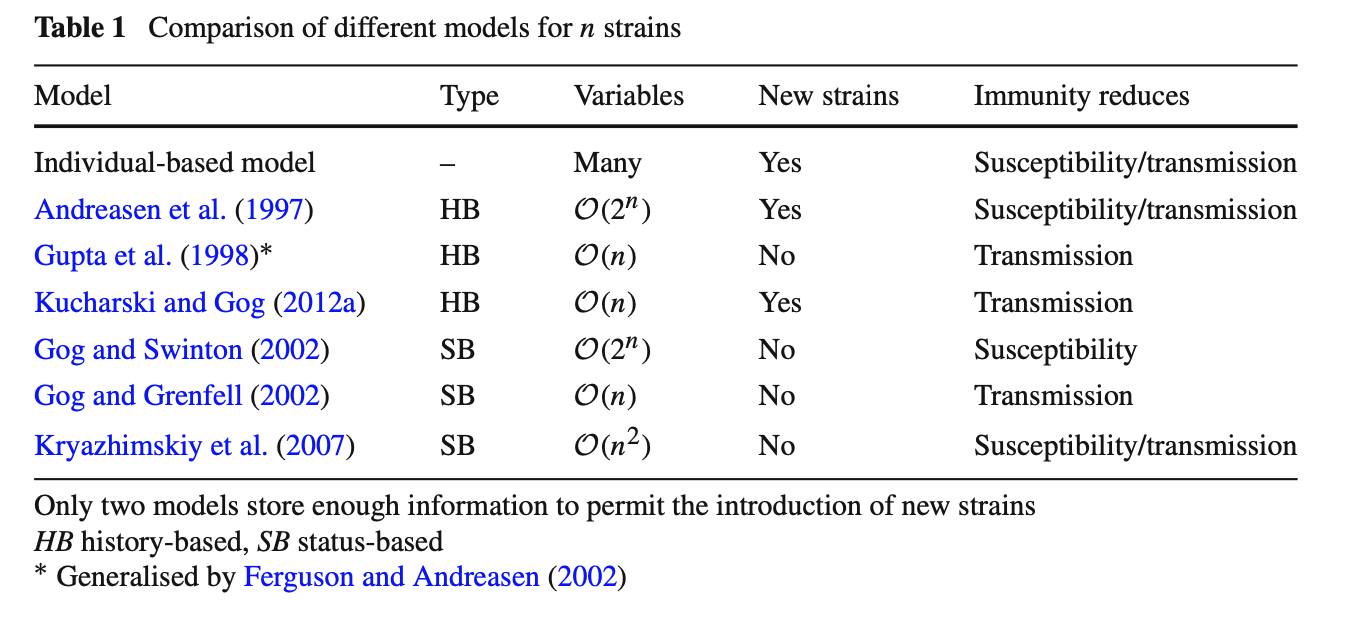

The main compartmental models currently available for exploring multiple strain dynamics are summarised in Table 1. Many of the models with few variables require that cross-immunity between strains acts to reduce transmission. The assumption of reduced transmission is mathematically convenient because it means immunity to one strain does not influence susceptibility to another. Hence immunity will only change the rate at which individual passes the infection on, and not their probability of being infected. If cross-immunity leads to a reduction in susceptibility, the crucial simplifications in Eqs. 19, 23 and 33 are no longer possible.

From a biological point of view the assumption of reduced transmission can be awkward (Ballesteros et al. 2009; Kryazhimskiy et al. 2007). This is because upon infection we expect two events: the host becoming ill and transmitting the disease, and the production of antibodies by host’s immune system. If the host already has immunity to that strain, their current antibodies might block infection without transmission or production of new antibodies occurring. Under the reduced infectivity assumption, immunity prevents an infected host from transmitting the virus, but does not prevent additional gain of immunity. This could lead to an overestimate of population immunity (Ballesteros et al. 2009). Despite this potential caveat, however, the dynamics of the history-based model appear to relatively insensitive to whether immunity is assumed to reduce transmission or susceptibility (Ferguson and Andreasen 2002).

Biologically plausible assumptions do not necessarily generate biologically plausible dynamics, and vice versa. Moreover, choosing between two biologically distinct assumptions—such as reduced susceptibility and transmission—can sometimes have a negligible effect on model dynamics. Strain models inevitably have to balance realism with tractability; it is therefore important to know how different simplifications and assumptions influence model predictions.

Incorporating pathogen evolution

Evolutionary dynamics

Statistical inference for seasonally-forced SIR models can be performed using disease case data and sequence data (Rasmussen et al. 2011).

Tags: Infectious Disease Modelling

Categories: Paper digest

Comments